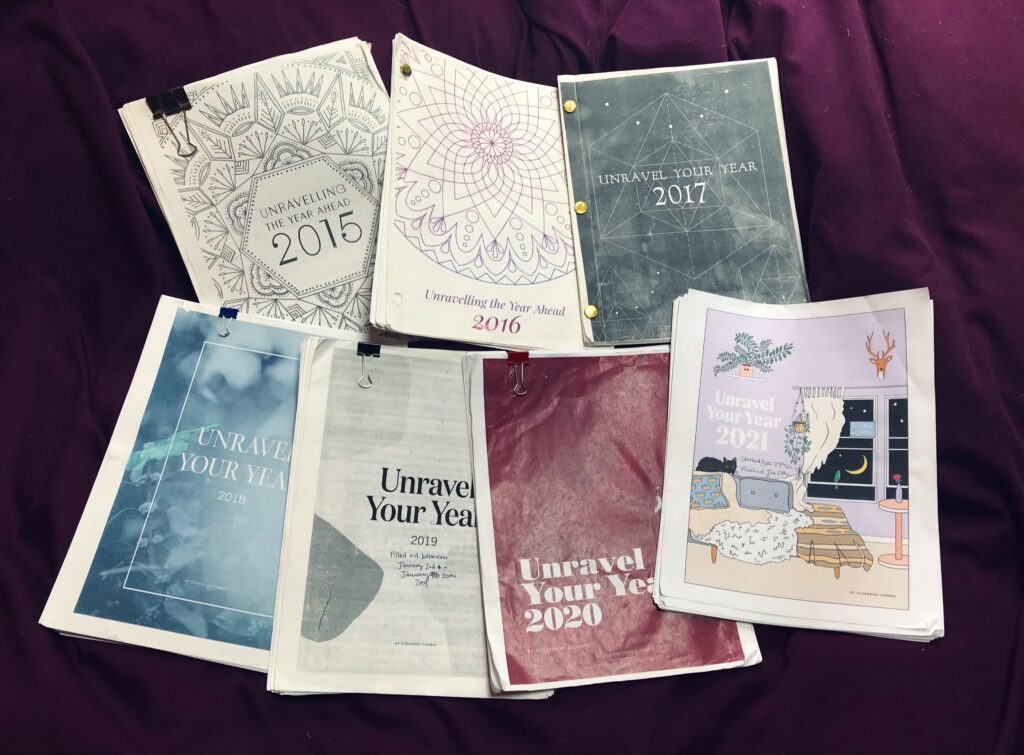

We think of people as settling down when they get older, getting more set in their ways. But that hasn’t been my experience. Instead as I get older, I’m itching to get weirder. I think that in my twenties, I was so determined to carve out space for myself in the world. And now that I have that space, I don’t really feel like I have anything to prove. So it’s safe to ask some big questions about who I actually am. I’m more up for rethinking what I thought I knew. I like the idea of not being content with the apples you can grasp.

Shay

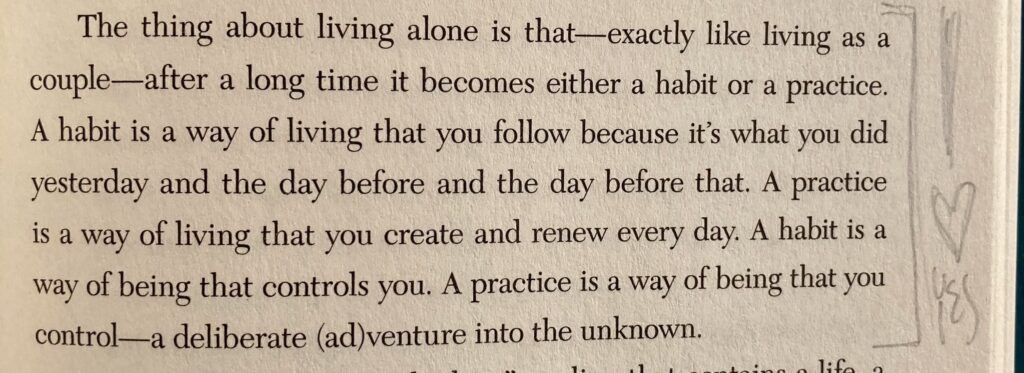

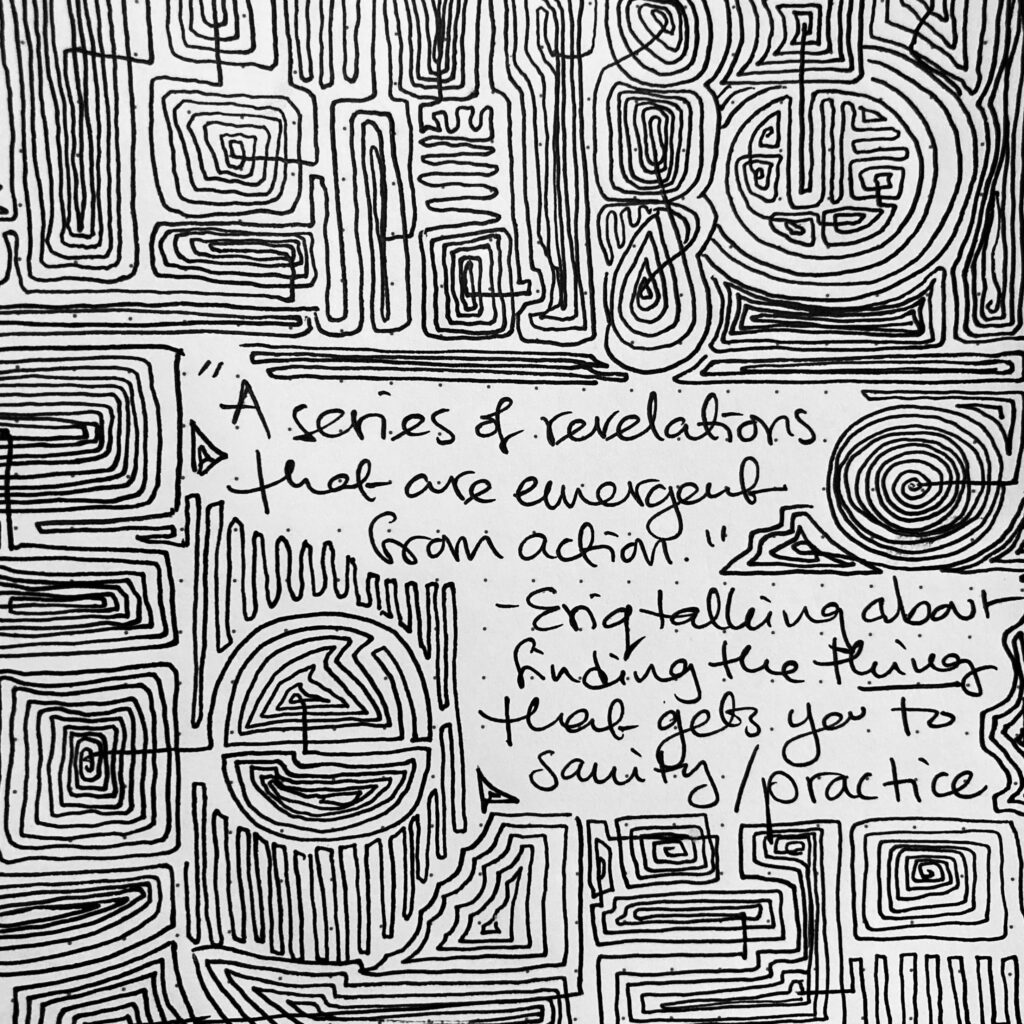

Is it that we actively pull ourselves into being by our very actions, our choices laying the foundations brick by brick for who we are and who we will become…?

Or is it that what pulls us into being, what pushes us toward action, is the ache, is our future selves, is the wisdom in our present yearning, foretold and prophesied by a future world who wants us to become who we inevitably need to become to create itself…?

Yes.

Christina

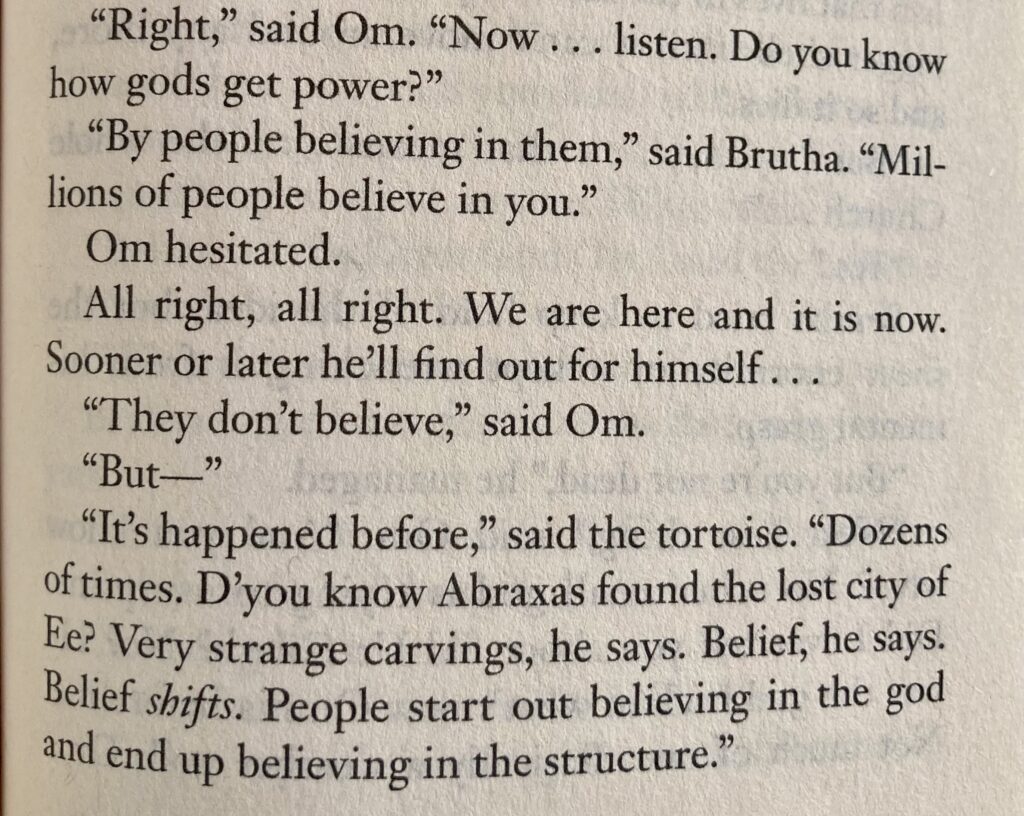

Maybe this swirl of awe and marvel and good intent for the world and gratitude for ourselves in it is where all the religions came from. That is where our feel for the sacred in the world is conjured, surely, the ordinary, staggering mystery of where it all comes from before it is born here among us and where it all goes after it dies away from us, the starry midnight courtship of the heart that whispers, “What is gone is still with you, still here. As you will be.”

Stephen

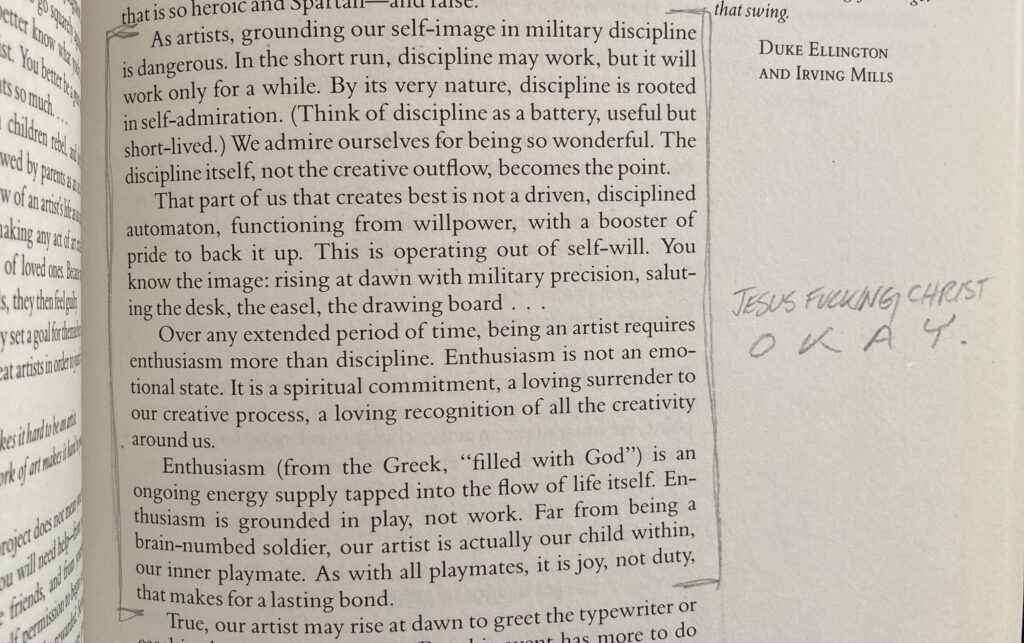

Not every experience needs to be put in the basket of “turn this into a beautiful piece of writing for the people”, but everything goes in the basket of – perhaps there is more to this than meets the eye.

Marlee

This is the inheritance that no one ever told you about—wild and curious, unblinking, sorrow-eyed and courageous chested, shuddering the rain from its feathers, ready to launch into the dusking light.

Martin