Category: Blog

If we could just—just stop. For one year. If everybody could stop publishing their poems. No more. Stop it. Just—everyone. Every poet. Just stop.

But of course that’s totally unfair to the poets who are just starting out. This may be their “wunderjahr.” This may be the year that they really find their voice. And I’m telling them to stop? No, that wouldn’t do.

But wouldn’t it be great? To have a moment to regroup and understand? Everybody would ask, Okie doke, what new poems am I going to read today? Sorry: none. There are no new poems. And so you’re thrown back onto what’s already there, and you look at what’s on your own shelves, that you bought maybe eight years ago, and you think, Have I really looked at this book? Might have something to it. And it’s there, it’s been waiting and waiting. Without any demonstration or clamor. No squeaky wheel. It’s just been waiting.

If everybody was silent for a year—if we could just stop this endless forward stumbling progress—wouldn’t we all be better people? I think probably so. I think the lack of poetry, the absence of poetry, the yearning to have something new, would be the best thing that could happen to our art. No poems for a solid year. Maybe two.

—Nicholson Baker, The Anthologist

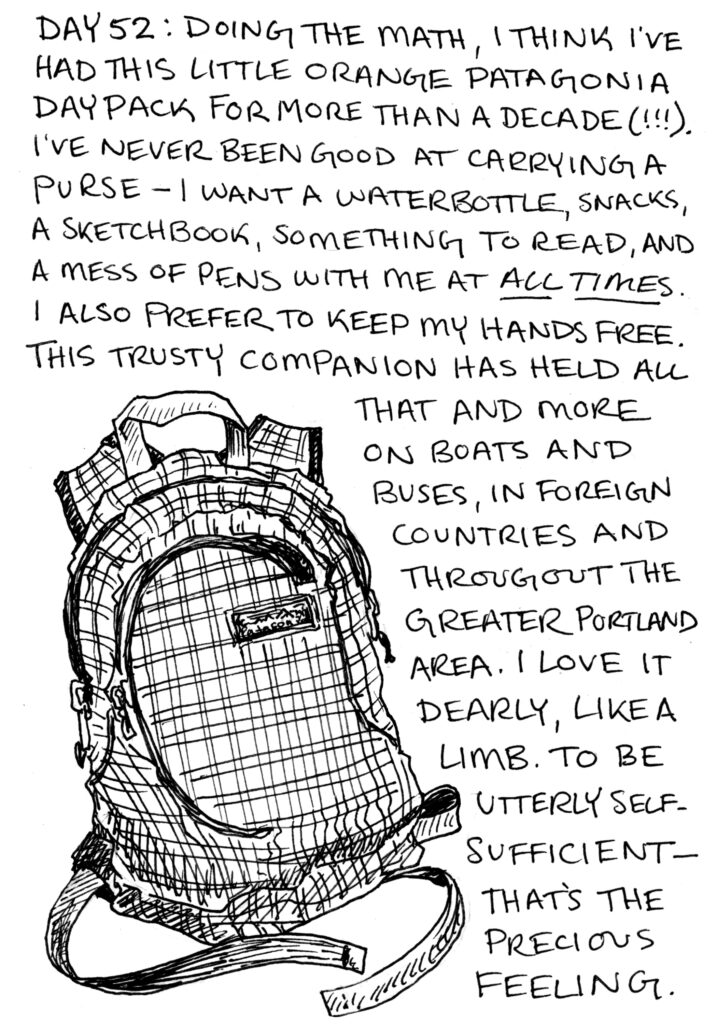

The bag in this photo is now old enough to drive.

I got it sometime early in high school, probably from the outdoor shop Riley’s mom managed down in Ventura. I eschewed carrying any kind of purse for years because I like keeping my arms and hands free to scramble about, and this little pack was a dream come true for that purpose. It’s just the right size to hold all my essential belongings: a water bottle, a sketchbook, my pens, snacks, a book, even (these days, when necessary) an iPad.1

It’s been down the Grand Canyon and across the Pacific Ocean, to conventions and signings, through endless TSA checkpoints, and to the Edinburgh hillside in this photo, where I passed a blissful and sunny afternoon in 2007.

But last week I came home to find the front panel shredded open thanks to the escalating Rodent Situation here at Bellwood Towers. I was heartbroken. Patagonia have a repair program where they’ll do their best to fix anything that’s gone wrong with their stuff for free (pretty cool!), but the wait times right now are long, and I couldn’t really imagine being without this thing for months on end. I could patch these little rodent holes myself—they’re not huge, after all—but the truth is, the bag’s seen better days.

The elastic is shot. The zipper pulls all broke off long ago. The inner lining is dingy and stained because I’ve never learned my lesson about which pens can and can’t survive air travel. The waist straps are missing because I cut them off to make a belt for my dad when we’d evacuated from the Thomas Fire and his trousers kept falling down.

And so I thought “What’s the harm in looking?” and opened eBay.

As you might expect for an item released in 2005: not a lot of options. Some from the same line, but inevitably in a larger size, and all of them black. The only similarly small one was $115. From Japan! Excessive. Unreasonable. I gave up.

And then the following morning I checked again. A bag! My bag! The same color (well, the color I guess my bag must’ve been once upon a time, though I’d never think it to look at them side by side), thirty bucks, shipping from Texas. Too good to be true.

I hit the button.

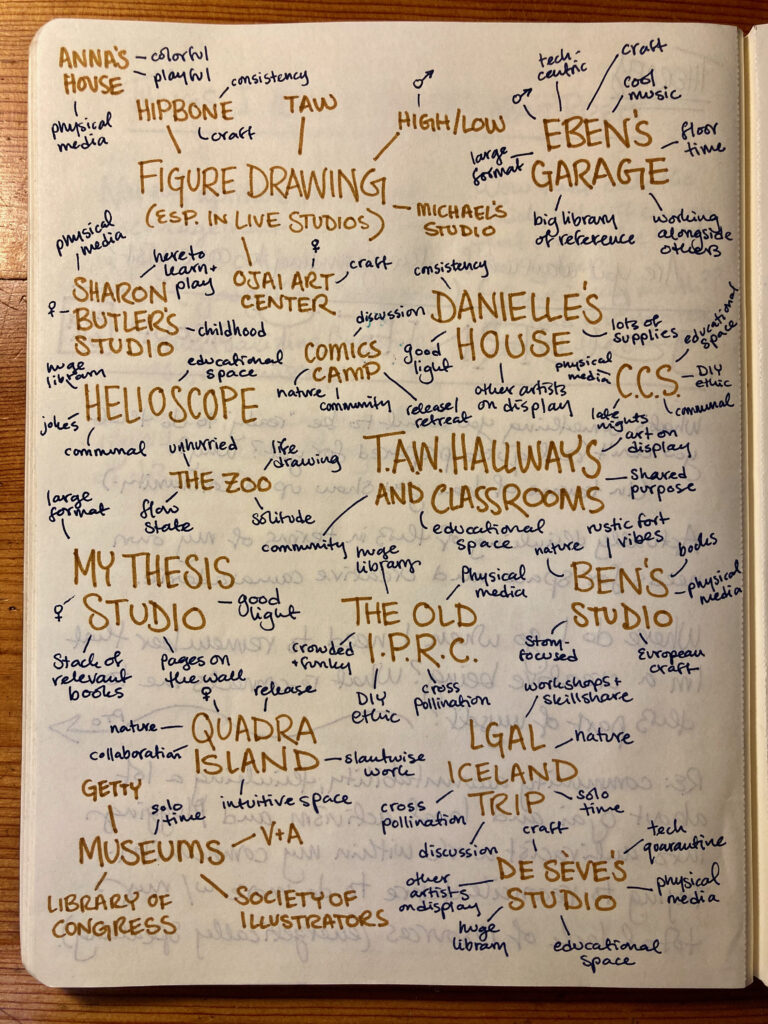

When I was working on A Life in Objects (my first 100 Day Project, back in 2016) it became very clear to me that I love long-term belongings. Partly it’s because I grew up in a very thrifty household and the idea of randomly replacing or upgrading things willy-nilly is blasphemy to Bellwood ears. But it’s also because I love the stories that trail behind oft-used and much-loved items. And yet: a huge benefit of that project was giving myself permission to let some of the profiled objects go after feeling like I’d preserved them for posterity in some small way.

In fact, I’m pretty sure I drew this backpack. Oh yeah, here it is: Day 52.

I guess my feelings about it haven’t really changed.

Anyway, I’m blogging about a tiny, ancient backpack because I want to give myself permission to take its replacement with me on my next adventure: a flight tomorrow morning, my first since February of 2020. I’m sure I’ll be twitchy and anxious under my double-masked exterior, trusting in two shots of vaccine to carry me across the country and back without incident, but I think there will also be a lot to appreciate. A lot to wonder at. I feel rusty, but renewed by this long break from going anywhere.

Tiny miracles. Old things made new again.

1. Hell, when I first got this bag the iPad hadn’t even been released. I didn’t own a cell phone. Different times. ↩

On a call with some of the folks from the Wayward community the other night, someone shared a conversation they’d had with their therapist about emerging into 2021. PTSD, the therapist pointed out, doesn’t generally rear its head while soldiers are on the battlefield. It comes later, when things are supposedly “safe” or “better” and everyone around us is celebrating or relaxing and we’re only just beginning to experience the full impact of what we’ve been through.

It hit me like a pile of bricks.

I feel so far away from my creative self right now. The only thing I keep finding comfort in is learning that a lot of other friends are in the same boat—that maybe a majority of us are actually grieving the loss of whatever creative spaciousness or clarity we’d managed to eke out in the solitude of Quarantine. Or maybe we’re all just braced for the next wave of closures and infections and losses, or finally feeling the full weight of the closures and infections and losses that have already come and gone.

My first family COVID deaths happened in quick succession within the last two weeks—far past the peak of the Pandemic. What does that mean? How am I supposed to feel? They lived in another country, separated by oceans and continents and the 17 years since I saw them last in person. But they were family—a community I struggle to feel connected to at the best of times, even though I yearn for it desperately. I’m vaccinated. My parents are vaccinated. Nothing quite like thinking you’re “safe” and then realizing grief can still snake its way into your circles, no matter the care you take.

I’m thinking, too, about the way I keep brushing off this mental and creative slump in conversation, waving my hands and explaining to friends that “it’s just a phase” and “things will feel better as soon as I get stuck into my next project.”

“This always happens,” I say. “I always pull through.”

But something I didn’t account for is living in house alongside my dad, one of my primary sources of creative inspiration and cheerleading growing up, who genuinely has lost contact his creative self. Dementia is not the seasonal cycle that I usually comfort myself with when I think of the ebb and flow of creative embodiment. It’s a far darker and more linear decline. It makes the threat of permanent loss in these low tide seasons feel more real.

It’s not to say that I’m over here worrying about imminently losing all my marbles. More that…I don’t know. Maybe that I haven’t been making enough space for the enormity of everything. When I make light of this season—either because I’m afraid of it, or embarrassed that it’s happening to me, or something else—I rob myself of the chance to feel my way through into whatever comes next.

What is created in my collection of touch and loss? Philosopher Jean Luc Nancy believed that writing is a form of touching. Through each page readers touch the writer, writers touch readers. As I write my archive I grasp for the ones I love. I pour every word with heat. I’ve always believed scholar of language Athur Quinn when he wrote “Language has all the suppleness of human flesh, and something of its warmth.” I savor the warmth or writing while yearning for another. I wrote a memory of holding my mother’s hand in prayer. I wrote the memory with my own hands now with skin thin, pliable, raised light blue veins. My own hands are aging, and I can’t remember when I last held my mother’s hand in mine.

—Patricia Fancher

Just a Shower Thought Addendum: I know we feel compelled to check in on people when they haven’t posted on social media in a while—as if that’s the best external marker of mental health—but what if being absent from social media was the healthy norm and anyone posting a great deal got showered with direct contact from their friends to find out if they were okay?

It feels redundant to keep pointing wildly at everyone who’s coming to similar conclusions about the instability of this online ecosystem right now—BUT—every time I find another person doing it I start yelling “YES. YES!” and do want to catalogue them in some way because these conversations are unfolding in many different spaces concurrently. It’s not just cartoonists writing about being cartoonists. It’s dancers and authors and comedians and zinesters and activists and journalists and musicians all pausing to look around and say, collectively, “What the fuck am I doing here?”

I’m thinking about comedian Bo Burnham’s remarkable special Inside. About choreographer and quilter Marlee Grace’s latest newsletter. Jia Tolentino’s “The I in the Internet“. Rain’s documentary The Shopkeeper. Mara’s “Sex, Husbandry, and the Infinite Scroll“. How to Do Nothing. The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. I could go on.

Robin called the other day and mentioned that I seemed to have stopped blogging, to which I say: it’s a fair cop. I was in Portland being consumed by my newfound ability to be close to other people and then I was moving and for the past ten days I’ve still been moving, but it’s the shitty back-end part of moving that we don’t talk about as much where you have to actually unpack and (in the case of this particular move) jettison decades of childhood ephemera from your tiny bedroom in order to make it a livable space for yourself as an adult.

The last piece of furniture I needed to move in was my bed frame, which I’d decided to stain and refinish because “Imperfect DIY Projects” was in my “More” column for this year. Now that I can sleep in a space with visible floor area and a desk I can actually sit at (though I am, in fact, writing this on the bed), it turns out my brain is far more capable of turning to the digital spaces I’ve been neglecting for the past six weeks. By returning to writing, I’m breathing a habitual sigh of relief—the kind that turns into a stream of words about shit I didn’t know I was even processing in the background of whatever I was busy doing while I was thinking that I’d never write another word ever again.1

So, after all that preamble:

Nicole Brinkley wrote this essay called Did Twitter Break YA? as part of her Misshelved series on Patreon and it’s fucking great. YA isn’t my community, but it’s adjacent to my community. And booksellers (the community Nicole talks about most frequently in her writing) are absolutely within my community. The patterns she describes in this piece—of context collapse and “morally motivated networked harassment” and parasocial relationships and burnout—are patterns I know like the back of my hand.

There are so many nod-inducing moments, but this was the one that really made my blood run cold:

After all, access to authors is the real product—and if an author missteps, they’re just a failed product. There are always more authors to fill that spot on the shelf.

Bluergh. Hurk. Ek. How often have I slipped into thinking of myself as a failed product on a shelf? Certainly every time I’ve stopped posting as often on Patreon, or expressed enthusiasm about doing a drawing challenge and then failed to follow through. Definitely in those moments when I think that if I just had a bit more energy and time I could start making content that would grow my following “in earnest”. When I take two years to send a new installment of my newsletter. When I disappear.

But it’s not just the disappearance. It’s feeling of one’s absence being invisible within the onrushing tide of Other People’s Output. Remember that Drew Austin essay I linked a couple posts ago? He gets into it there, noting that “Every social media feed is an endless parade of these fragmentary identities, disaggregated into units of content and passing by quickly enough to evade the scrutiny that would detect their incompleteness.” The incompleteness being that we are all also doing and contending with other things. We have to be. We’re not just on Twitter 24/7—even people who seem as if they are.

This is the price of trying to succeed within the ecosystem of capitalism, and maybe it’s also why I want to keep sharing here and here alone: I haven’t contaminated this container yet. It gets to sit apart from everything else, just me and my thoughts.2

Earlier in the Pandemic Mara made a rare Instagram appearance, posting a series of text-based stories from her new home in Winthrop, Washington. I transcribed them immediately because, as with most things she writes and shares and speaks about, it sparked something in me that I needed to sit with for a long time.

I have so enjoyed every story and post by you all, dear friends. How does it work when I just observe you, and when to like/comment on what you make here is to feed an algorithm that watches and profits off of our affection? I don’t do it because it feels…violent?…to us. This platform is very hard for me. Thank you for understanding. It pales in comparison to being near you. The simulacrum of closeness feels nauseating. I know we are killing something important in the process of creating connection. I want you to walk through the door, for us to play. You’re all here always.

This is it—the heart of the thing. We chase engagement as if it’s the Holy Grail, and yet to play the game on any level means we’ve already lost. There are so many people I can think of who I’ve finally been able to see and embrace and laugh with over the past month and attempting to get that through social media does pale in comparison. The simulacrum is nauseating.

This handful of broken online platforms can’t be everything.

Past a certain point I don’t want to spend my time cataloguing people’s writing about this—or generating my own—because (and this is the curse of the over-informed over-thinker) I know it all already. I know it in my bones. I may not have the right terminology for it, but I can feel it. I fear I am admiring the problem, thrilling to ever more accurate descriptors that tell me precisely how and why I’m locked in this unfulfilling spiral, rather than taking steps to change my behavior.3

As Tolentino points out, “The internet reminds us on a daily basis that it is not at all rewarding to become aware of problems that you have no reasonable hope of solving.”

But Nicole is ready for that.

[…] I do not want to wear the armor of cynicism. I do not want to be trapped in the ouroboros of perfection just because the community I interact with demands it.

So here is what I will say to you, dear reader: You do not have to participate in this cycle.

The system is broken, but the system can be abandoned.

In addressing this head-on, she wins my heart.4 She admits that the piece started out as one thing and then turned into another. She describes the trajectory it might have taken had she chosen to focus solely on the issue of where actual teenage readers sit in the modern YA landscape, and then she recognizes that this is really a conversation about so much more. (I will never stop loving this pattern, wherever I encounter it.)

The Fake-It-Till-You-Make-It School, the Grit School, the Capitalism School—they all urge us to keep producing and grinding and persevering, trusting that clarity will come from more work (even if that work, at its core, is purposeless, unfulfilling, or even actively harmful). With no time to reflect or catch our breath, we feel we have no choice but to trust the systems we’re given, to push and push and push until we “break into” the spaces that are communally regarded as desirable, and then fight like hell to keep that power safe because don’t you know this is a landscape of scarcity? There’s only so much to go around.

When I think about the last year, I don’t think about pushing. I think about waiting.

I had to wait. I had to wait a long, long time. In some ways I’m still waiting.

So when Nicole says:

These days it’s okay to not be sure what Twitter is for. We can stop going there until we figure it out.

It feels like permission.

It makes my soul exhale.

“I don’t feel good when I’m here” is enough of a reason to leave. Even if the places I wish I could stay—or the people I wish I could stay with—sometimes bring me connection and joy and validation and money and, yes, even love. If my gut tells me that I am not, at baseline, nourished the way I need to be: I can walk.

That’s the new rule.

Thank you, Nicole.

1. I’m also kind of glossing over the fact that my obsessive nesting has masked a deeper discomfort with having to face the true emotional cost of this transition. That’s a conversation for another time. But, as my therapist reminded me: this grief is chronic, not acute. Avoidance is a tactic we use to survive ongoing adversity. It’s not inherently evil. ↩

2. Also, just a general side note in relation to all this: how often have I shared something like Nicole’s essay on Twitter or Instagram with the caveat “I’m fully aware of the irony of sharing this here, but…”? I want to stop doing that. If I’m reading something about how fucked it feels to still be on a certain platform and it resonates with me, I WANT TO TALK ABOUT IT SOMEWHERE OTHER THAN THAT PLATFORM. (I am yelling at myself here because this is a footnote and that’s what they’re for, I think.) ↩

3. Whoops this is the moment I realized that this essay is also about my historical approach to relationships. Surprise! ↩

4. She also reminds me of this stunning essay from adrienne maree brown about disrupting patterns of harm that specifically target Black women within movement work. I’m due a re-read because I haven’t stopped thinking about it for months. ↩

I don’t know how I ever forgot about this perfect blog, but James reminded me of its existence last week and I’ve been weeping with mirth at every deranged entry ever since. There’s something about this particular cadence of humor that reduces me to rubble. Maybe you were around on Tumblr in 2015 and have already been thinking of it constantly for the past six years. But if you, like me, had forgotten? Well.

Something I frequently joke about—a dark truth that begs for humor—is how social media requires continuous posting just to remind everyone else you exist. I once said that if Twitter was real life our bodies would always be slowly shrinking, and tweeting more would be the only way to make ourselves bigger again. We can always opt out of this arrangement, of course, and live happily in meatspace, but that is precisely the point: Offline we exist by default; online we have to post our way into selfhood.

I’d never read anything by Drew Austin before today but boy howdy this got me right in the brain stem. Where and who and what am I these days, when I’m not sharing nearly so much of my life online? Am I coming into a season where my online persona is failing to cohere? Is that coherence even required on a personal blog in the same way it might be on social media? I have a lot of selves, and the task of reconciling them in the real world is daunting enough—let alone attempting to reflect them all equally in the weird hall of mirrors that constitutes online living.

Even before the Pandemic, I spent a great deal of time finding connection through machines. It was part and parcel of my work, the backbone of my audience and my ability to make a living. But having spent the past year being forced to mediate all my relationships through the internet or the telephone has left me hungry for connection in space in ways I can’t fully articulate.

Don’t get me wrong: I learned so much over the past year. From Kat. From Rachel. From Erika and Danielle and Robin and James and Sarah and Zina and Jez and Tess and Kristen and Vivian and RSS and Wayward and Hyperlink and everyone. I deepened and renewed and began so many friendships. So it’s a little surprising to me that I’ve had barely any interest in opening my laptop or getting on social media in weeks.

The obvious reason is that I’m currently moving out of my home in Portland for good. My days are full of boxes and warehouses and logistics and flaky Craigslist randos. But beyond the chaos of the move, there’s also the fact that in this post-vaccine, pre-moving-to-Ojai-for-the-long-haul moment, I’m being given the chance to reengage with the physical world—with my flesh-and-blood Portland humans who can give each other hugs and cook together and dance and laugh and cry in the same space. It’s commanding absolutely all of my attention.

I don’t even miss the internet. It feels so strange after a year of feeling like it was my lifeline.