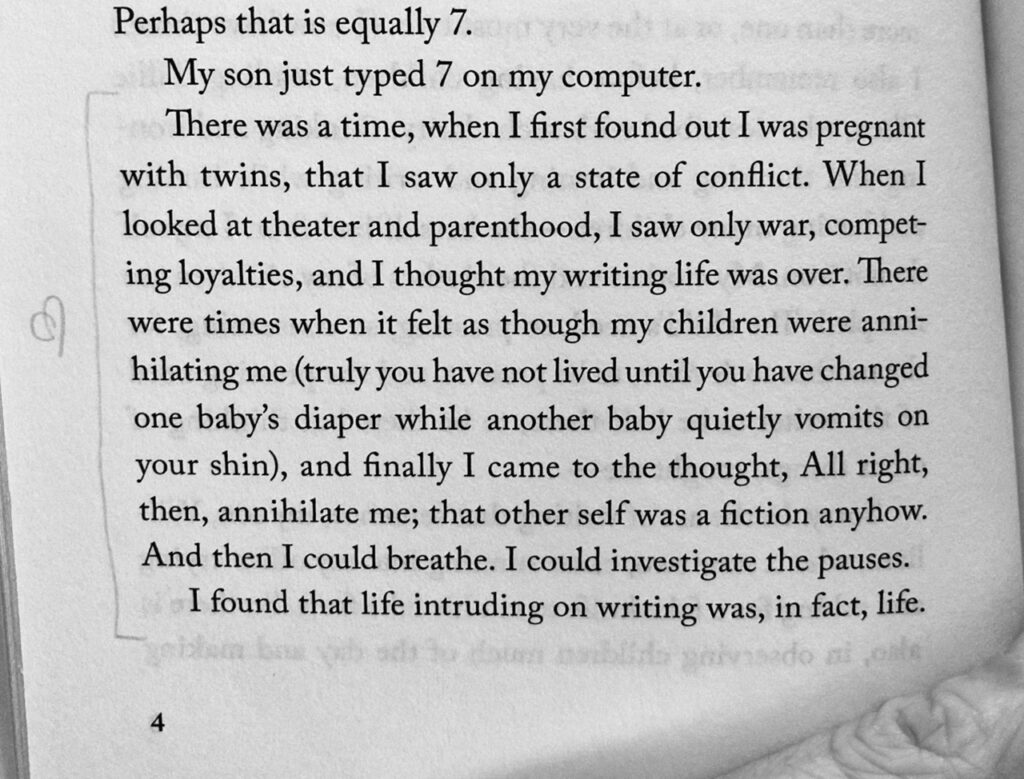

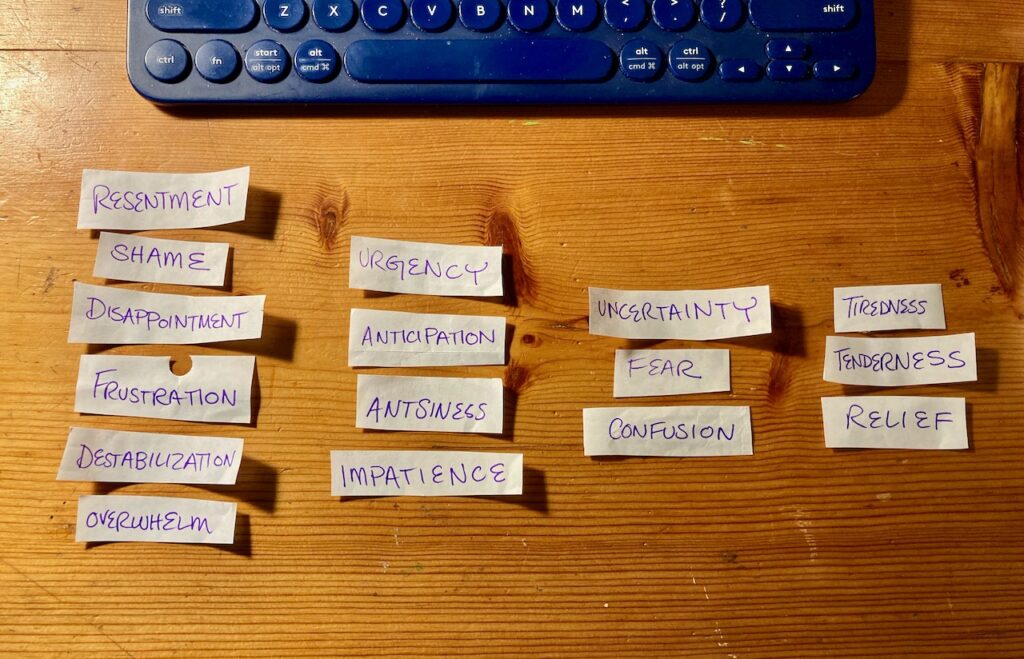

Exactly one year before I started drafting this post (which then languished for a little while, so technically now it’s more than a year ago, but whatever you get the idea) I wrote a short thread on Twitter about feelings and impermanence. I dug it up because I came across this photo and couldn’t remember what the hell I was doing that led me to group these little slips of paper in this kind of configuration. I’ve copied the thread verbatim below.

“Did an exercise in therapy this morning where my therapist asked me to list all the feelings running through my brain/body on bits of paper. Spent the rest of the session sorting them into affinity stacks while we talked.

It got me thinking about Chronic Feelings vs. Current Feelings. These are current, influenced by the hospital visit this week, the slow return to stability after a trauma, my anxiety about understanding my family’s finances, an impending trip, a disappointing career decision.

The Chronic Feelings are things like anticipatory grief, professional burnout, climate anxiety, hatred of capitalism, Pandemic Fatigue. The stuff we’re all collectively steeping in that constitutes a full emotional plate on its own.

But to try and be present with the feelings in my body right NOW requires a different sort of lens. It requires understanding that all of this passes.

I get reliably down most afternoons. Eating lunch triggers a slump of despair and exhaustion that isn’t the end of the world. It’s rare that I feel dreadful while I’m having my tea and scrawling pages into my journal outside in the sun first thing in the morning, so whatever’s coming for me today will, at the very least, abate for a half hour tomorrow. This helps to remember.

I have many weird/bad feelings about Twitter but also I think a lot about the people I know on here who’ve been generous enough to share their complex emotional stuff over the years. Folks grieving in public, folks naming anxiety, folks sharing their affirmations. It’s important.

A big cornerstone of how I’ve carried myself online for years has been an emphasis on sharing clear, proactive, hopeful things. Sometimes I fear this season of my life is going to break that, because it’s HARD. But I do think there are still ways to approach it with that ethic.”

Weird to still be chewing on the same stuff a year later. Weird to still be in an endless rollercoaster of absurdity and grief with my dad. Weird, also, to see the cadence of tweeting transposed onto my blog. Writing like that doesn’t belong here! But also I engaged in it for so many years on that platform. Every container nurtures its own syntax.

A friend asked if I’d signed up for Bluesky and the wave of exhaustion I felt in response washed the flesh clean off my bones. It’s not just that Twitter seems to be continually on fire these days, it’s the broader truth that social media feels hollow to me now. The ADS! There are so many ads. Why did I ever put up with a space that was so aggressively trying to sell me things at every turn? (The answer is that it was giving me the Good Brain Chemicals when I interacted with people I care about, but these days I don’t post enough to get notifications, so I’m trading my attention for NOTHING! No wonder the shine has worn off.)

I’ve been thinking about this installment of Holly Whitaker’s newsletter ever since I read it a couple weeks ago. I haven’t even dug into the links, but the dislocation theory of addiction latched onto my brain stem and has yet to let go.

Our modern social arrangement, Alexander argues, means that we have to sacrifice “family, friends, meaning, and values” in order to be more “efficient” and “competitive” in the rat race. In this framework, addictive behaviors are adaptive responses meant to fill that void of meaning and purpose. Using substances can provide a temporary sense of community (with other users), purpose (to acquire the substance), and meaning (feelings of euphoria or calm from using the substance). Substance abuse and addiction help to fill the gaps in meaning and purpose left by modern society.

None of this is news to me, really, but the articulation slotted something into focus. Reflecting on consumerism as an addiction (or maybe….everything as an addiction?) this month has been a valuable touch point.

And then here I am hitting go on a reprint of my graphic novel! A product I must then sell! A product I might even sell on the premise that it will make people feel less alone! HNGNNNGNNHHGHHH.

(I was going to expand on stuff in that tweet thread in this post too, but I got sidetracked and now it’s time to make my dad his breakfast so I’m hitting post because there are no ads here and nobody needs to buy anything and it’s one of those days where I want to move to the woods and eat grubs for the rest of my life so byeeeeee)