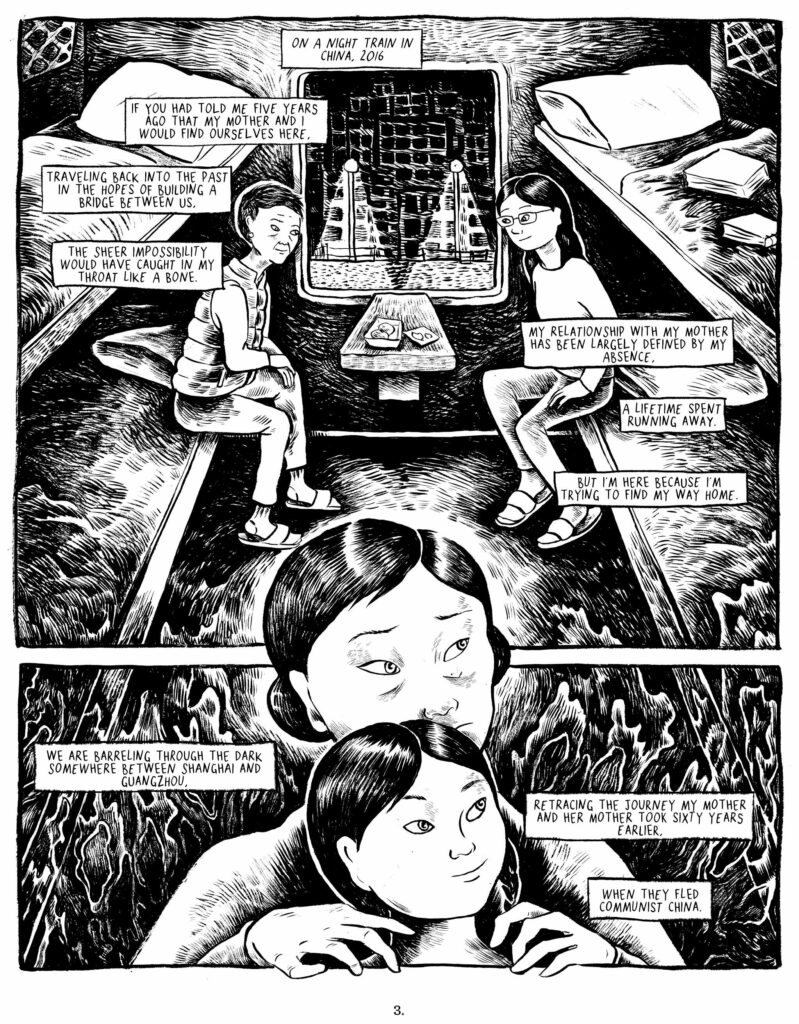

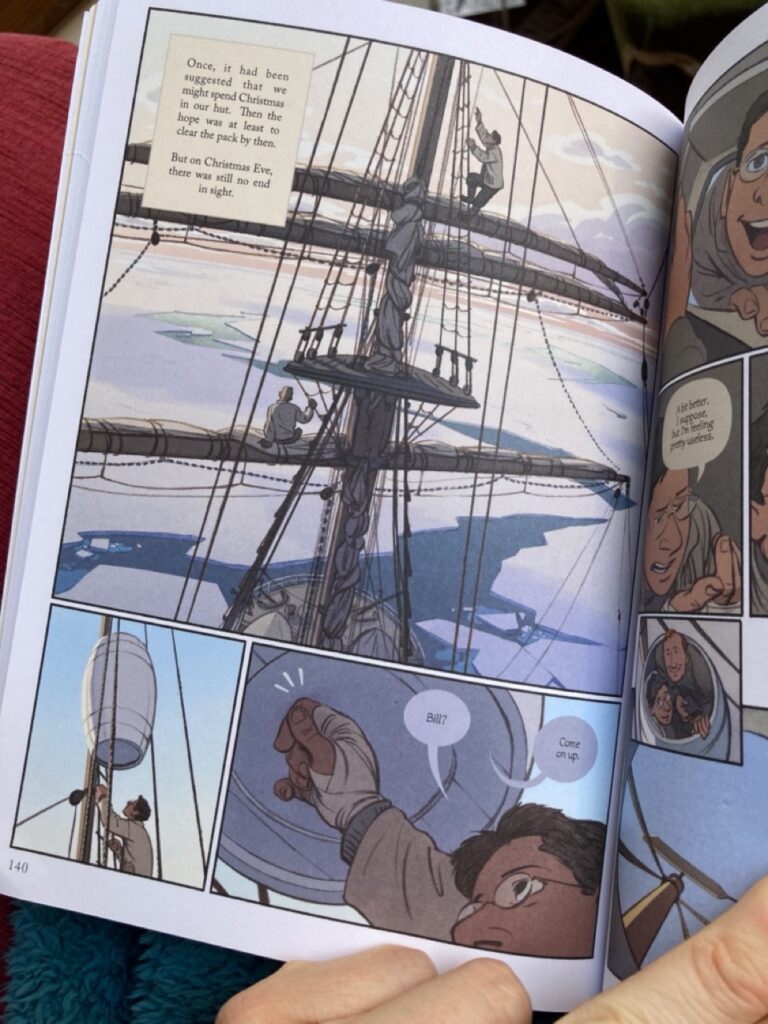

It’s happening again, the thing that happens when I get back to drawing after a slump.

The transition was abrupt. I woke up two weeks ago, went to the studio, queued up Neil Gaiman’s live reading of The Graveyard Book (my habitual comfort food of many years), cranked out four pages, rode my stationary bike for a half hour, and then took it upon myself to begin eating a whole head of lettuce every day to finally get ahead of our CSA box. The transition was shocking in its ease, especially when I hold it up beside weeks and weeks of disruption and self-judgement. I’ve been torn between dog-sitting gigs, two different living situations, visits from friends, heart procedures at the hospital with my dad, studio moves, traveling out of state for events, and passing obsessions with whittling, ultralight backpacking, and quilting scattered in between.

Writing it all out, I soften. Of course I’ve struggled to sink into the kind of flow state needed for real progress on my book. There’s been no consistency! No ritual! No routine! My poor little animal brain doesn’t know how to make sense of it all.

But now that the gears have clicked into place and I’m suddenly off to work every morning like clockwork, the other thing happens: I lock down. I become superstitious and squirrelly, prone to evading all well-meaning attempts at conversation from the people I love.

“How’d it go at the studio today?”

“What’s your page goal this week?”

“When are you heading to work?”

Too much scrutiny makes me fearful. The ease of transition is suspicious. How did this happen? Why did I magically wake up and find it simple to return to work on this day of all days? If I don’t understand it, anything might switch it off again. So I err on the side of secrecy, and remain a jealous guardian of my time.

It’s been two weeks of consistent creative flow. It’s working for now. I’ll bask in it for as long as it lasts.