I’ll say it: I’ve been stuck.

In some ways I’m always stuck and just engaged in various stages of trying to wrestle myself free, but lately I’ve felt really stuck.

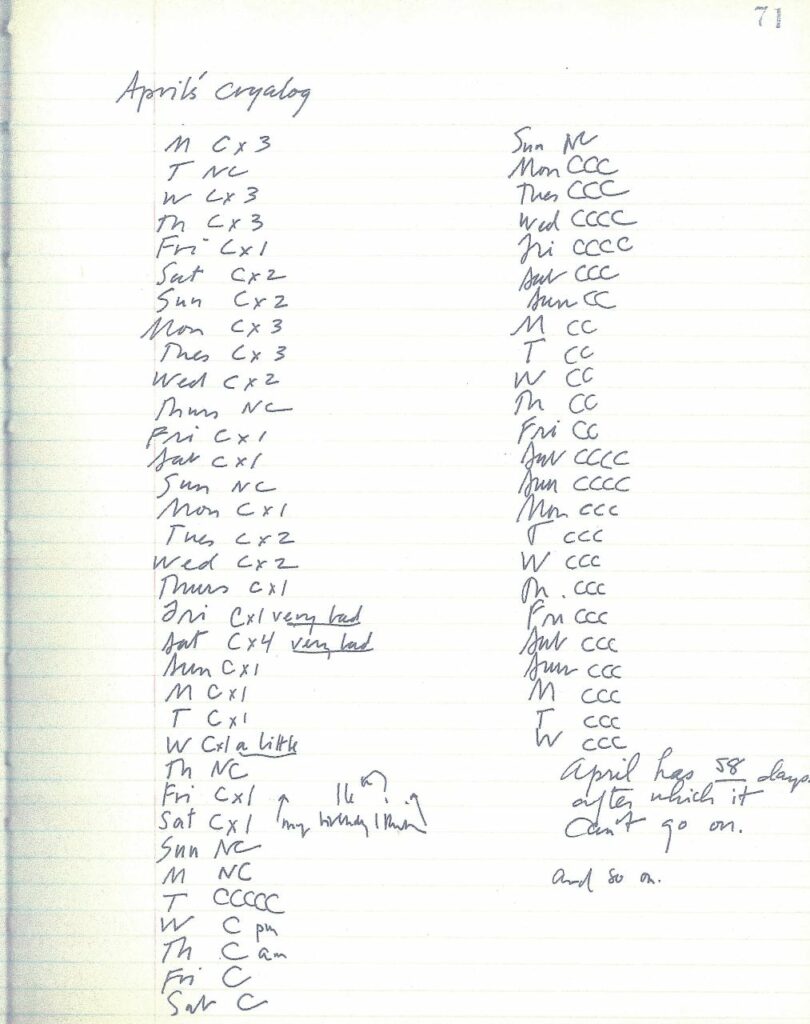

I cracked James Kochalka’s The Cute Manifesto in the studio a couple weeks ago because I’ve been trying to revisit formative reads from my early years of making comics and I couldn’t remember anything about it beyond a vague sense that it had been Important to me (although I was never really a dedicated reader of American Elf). The first piece is this:

“Craft is the Enemy” was originally published as a letter to The Comics Journal in 1996. It sparked a textual brawl between several readers and cartoonists (all, as far as I can tell, men) that lasted for months afterward. TCJ published an archive of all the letters on their blog, Blood and Thunder: Craft is the Enemy.

The debate exhausted me just skimming it.

I didn’t know about the fight when I opened the book. I just knew that somehow, a quarter of a century later, I was still the target audience for certain parts of this message: someone so prone to getting sidetracked by her own perfectionism that she was forgetting why she’d even walked into the room.

I am fucking petrified of starting work on my next project. I feel convinced that it won’t measure up to the standards of professionalism I’ve been cultivating from my own internal scripts and the constant barrage of everyone’s best selves on social media. I am someone who desperately needs the reminder that I have the tools I need to make comics RIGHT NOW, even if they don’t turn out the way I imagine they “should”.

And look, before anyone brings it up, yes, I’ve been the person giving this reminder to others in the past. But it’s a role that’s hard for me to occupy right now. I needed to hear it from someone else. I needed it because I have plenty of proof that I’ll do well if I turn my attention to a project or task at hand, and that knowledge becomes a prison. Every project must be bigger and better than the one before. The line must go up and to the right. If you did well before you must do better now. The practice gets harder, not easier.

I fret and pace and gnaw my fingernails thinking about how much work it will take to cultivate the craft I think I need to make the thing I want to make the way I imagine making it, but no amount of craft will save me from the truth: nothing has EVER come out exactly the way I picture it in my brain. Not once. Every single time it’s a surprise. And I know from reading other artists’ accounts of their practice that this will continue to be true for the rest of my life.

This is the struggle, but it’s also the joy of the work. It’s endemic to the practice. It’s a liberation.

Why do I keep forgetting?

I don’t want to obsess about what will make my work perfect. That’s an impossible benchmark. I want to engage with the parts of the process that bring me joy. I want to tell stories. I want to explore with words and pictures. I want to get closer while still knowing I’ll never reach the finish line. A lot of the time this goal makes me think of Hokusai:

[…] all I have done before the age of seventy is not worth bothering with. At seventy-five I’ll have learned something of the pattern of nature, of animals, of plants, of trees, birds, fish and insects. When I am eighty you will see real progress. At ninety I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At one hundred, I shall be a marvellous artist. At 110, everything I create; a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before.

And yet, even he fell prey to it—right to the end.

If heaven had granted me five more years, I could have become a real painter.

I’m trying to keep skipping back and forth between dedication and gentleness, discipline and play. That’s what makes it a practice. Ním recently finished writing his Theory of Conceptual Labor after years of exploration and refinement. There’s a lot of craft at work there, but the text itself is also about this nebulous space of flitting from adherence to exploration and back again. (Writing about the Theory is a whole post in itself, so I’ll leave it for now, but I couldn’t not throw it in here.)

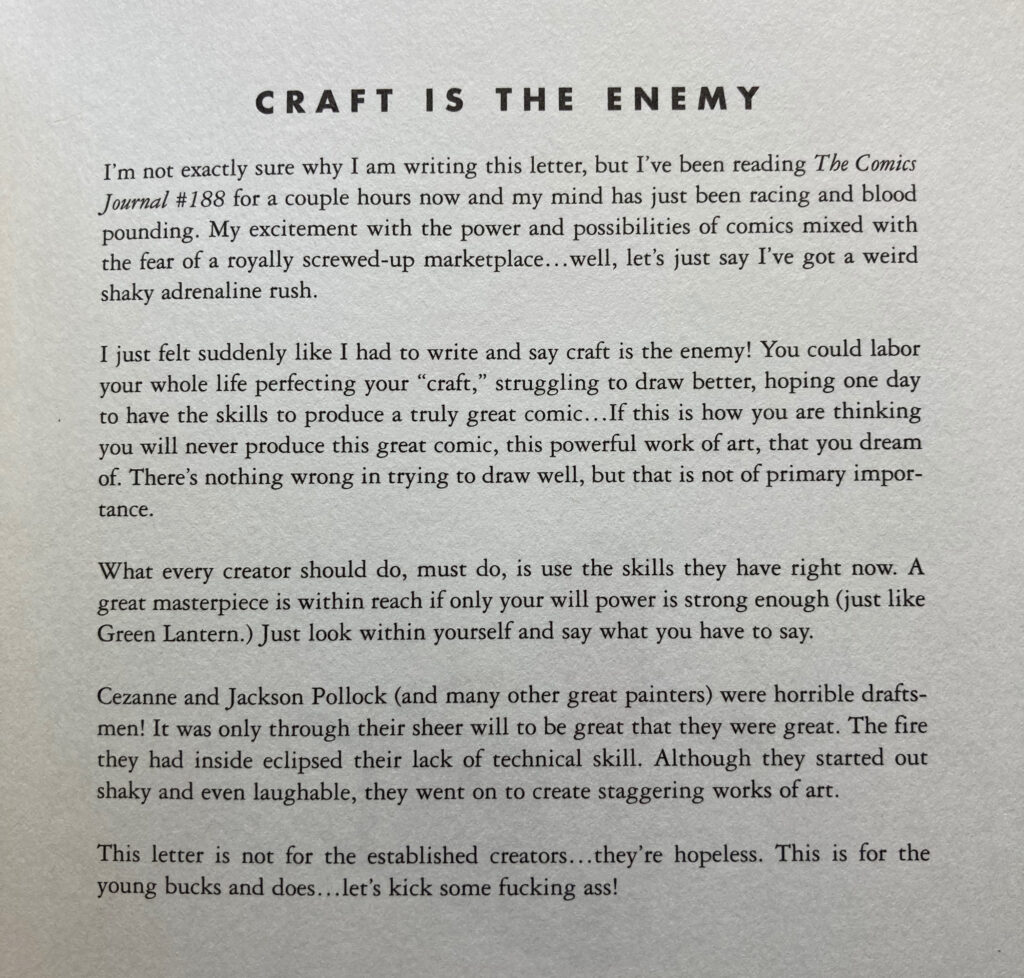

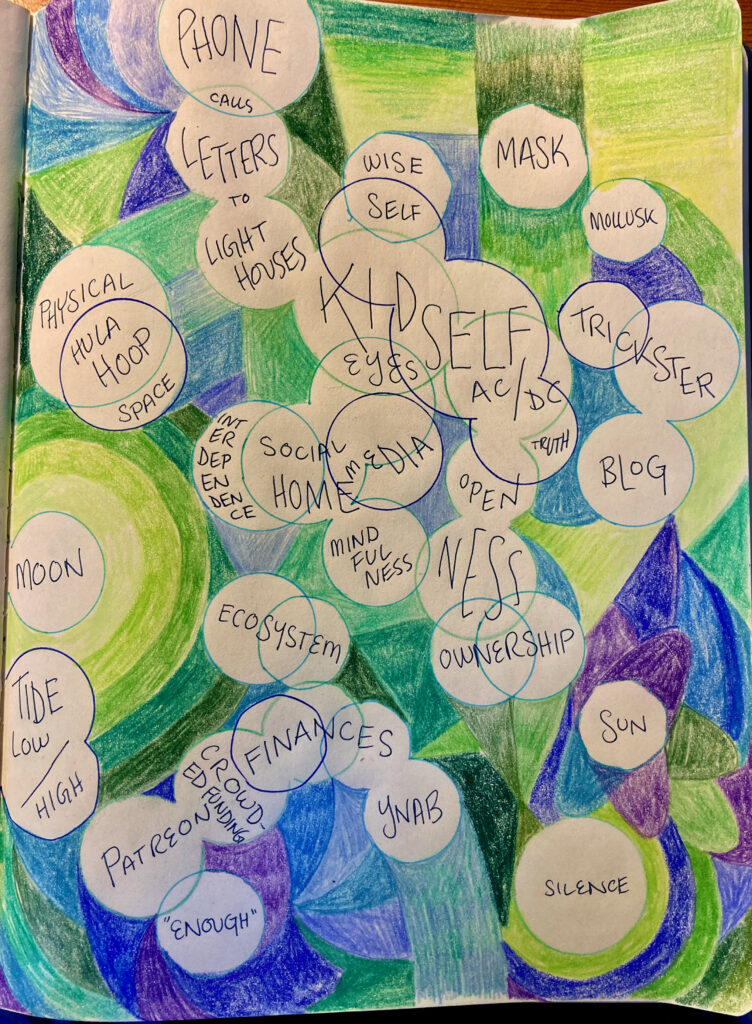

Years ago, on Twitter, I polled people on how they’d describe their relationship to creativity. I asked whether it felt like a job or an obsession or a calling. Everyone who responded to that poll had their own suggestions to include. I’ve thrown them all together into a loose mind map below:

This whole map feels true.

I have, at varying times, thought of myself as a craftsperson, a business owner, a religious zealot, a hack. I’ve pored over pages and relished the presence of thoughtful choices in composition and line weight. I’ve also seen the toll a dedication to craft can take on someone who’s being crushed in the vice of a traditional publishing deadline. I’ve copied and pasted and traced. I’ve insisted on using an Ames guide. I’ve worked digitally. I’ve worked traditionally. I want all of it. Is that so bad?

The roundup of letters from TCJ feels so deeply, seriously (and often cruelly and condescendingly) concerned with Rightness. Who is going to win in this fight? I wonder whether there’s more room these days for “This advice is exactly what some people need to hear, and for some other people thinking of comics as a craft is what THEY need to hear”.

Like…why fight about it? The relationship is between you and your work. What works FOR YOU in THIS MOMENT?

And then I realize where I’ve seen this pattern before. It reminds me of the ways I see queerness operating in our culture right now—working as a verb. There is, of course, still a lot of Discourse about identity and rulesets and gender and all the rest of it. The same patterns of policing abound. But I also feel like the increasing queerness of these spaces makes more room for a mentality of Yes, And instead of Either/Or.

When I look at the immeasurable wealth of queer identities and relationships and backgrounds at play in my circles, I see an enormous field of willingness to accept paradox. I see people engaging deeply and earnestly with the question of how they want to be seen and what they want to be called and who they want to get into bed with and how they want to love and where they want to fit in, but really, far more importantly, what makes them happy.

And I see people supporting each other by applying a simple metric:

“Does this nourish you? If so, I celebrate it.”

It makes so much sense to me.

When Tom Spurgeon interviewed Kochalka in 2008, he closed by asking whether craft was still the enemy. Kochalka replied:

Yes. However, because I draw so much, so hard, I almost can’t help but to improve my chops and solidify my craft. I have to purposefully cultivate a situation where I can still be surprised, where the new and unexpected sneaks in and overpowers my years of experience.

Some people are very concerned about mapping and naming, plotting and quantifying. I run the risk of being that kind of person from time to time, too. Someone asked me the other day how long I’d been in unconventional relationships and I struggled to answer. I felt that pressure to be able to explain. To know.

But I never felt like I had a good name for what I wanted, so I just kept stumbling along a path without a map, until one day I looked up and found myself somewhere that felt like home. These are the ways queerness operates: by circumventing the boundaries of the expected. By overpowering experience.

Anyway, craft and queerness. Yes, And. Forage for what feeds you, leave the rest.

Let’s go make comics.