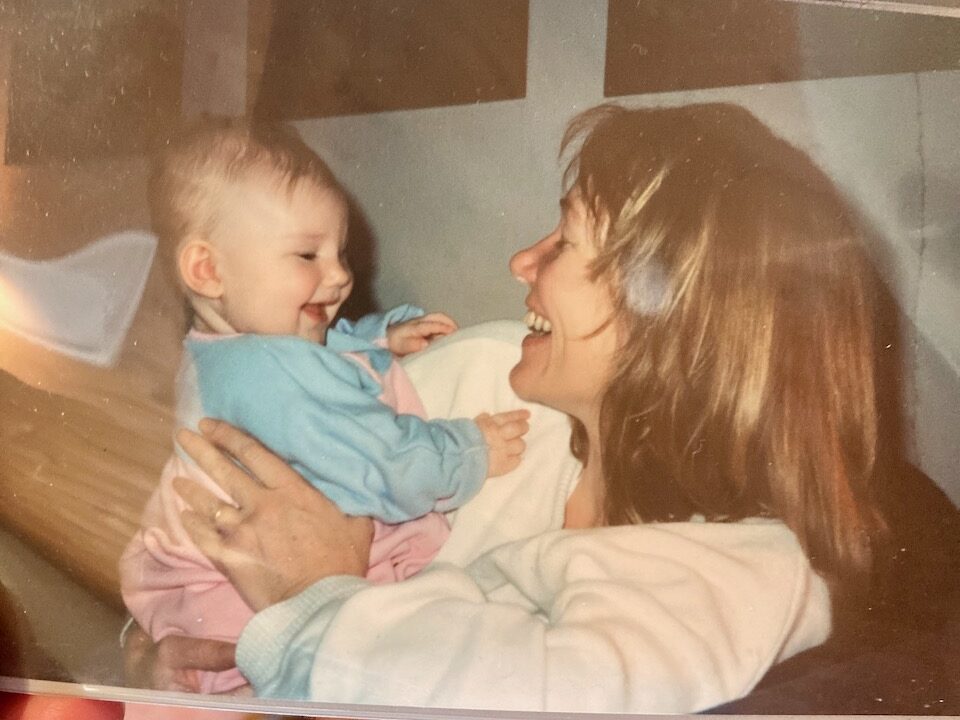

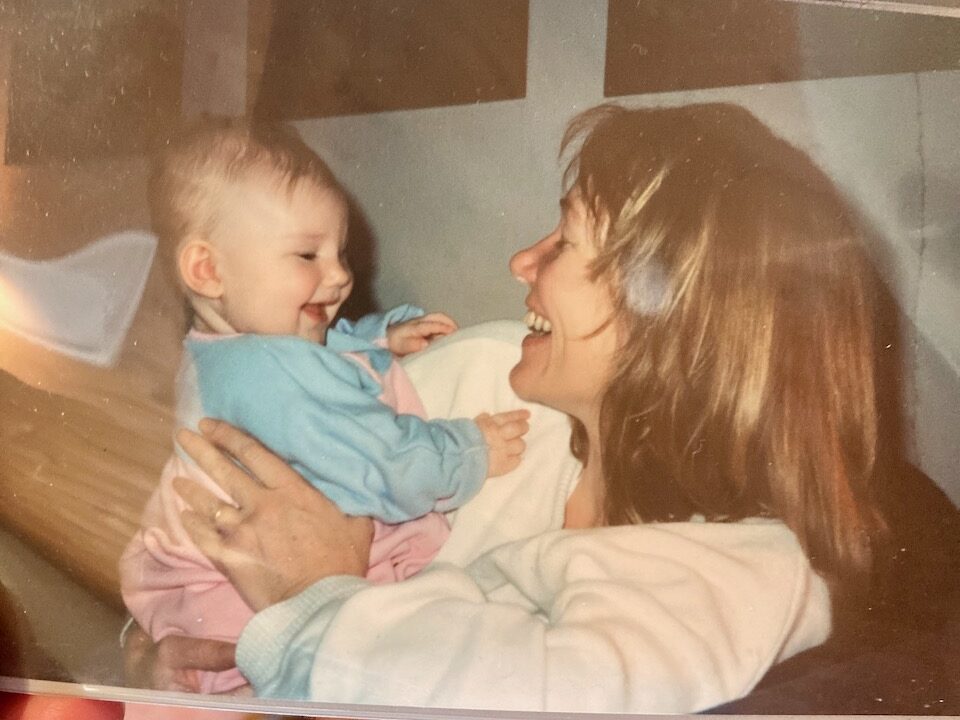

I feel so much tenderness toward these photos.

The online home of Adventure Cartoonist Lucy Bellwood

I feel so much tenderness toward these photos.

A few rhyming pieces from this week:

1. Sarah wrote a lovely, somewhat bittersweet post about finally closing her Photobucket account, which touched on a lot of what I find difficult about maintaining an archive of one’s creative work online as an artist, rather than just a writer:

I’ve never been sentimental about my childhood homes, but I imagine this is how it feels to leave one. I invested a lot more emotion into these drawings and writings than I ever did any actual geography; it was a (virtual) dwelling and a social life and autobiography all rolled into one. My blog archive and my long-defunct website, cosy and reliable home bases for so long, foundational in so many different ways to my identity, will be floating out there in the deep web without their illustrations, like abandoned buildings with hollow windows; it feels like I’ve pressed a button that sent them instantaneously into ruin.

2. Earlier this week, Brendan linked to Wesley’s writing, which led me in turn to their exploration of How Websites Die (which, in turn, referenced Winnie’s writing, whose work I only found recently through strange, roundabout blogging connections—did you know I love this game?). Timely to see that there’s a group of people all wondering about how we can (or if we should) make these spaces more enduring. Are they even built for that?

3. All these things led to thinking about how I do know someone who, out of a sense of love and duty and grief and stewardship, ensures that Chloe Weil’s site remains online, even eight years after her death.

I think the web is full of these silent acts of affection, but they can be hard to see.

I’m starting to think I have a knack for digital bibliomancy—an uncanny ability, given the vastness and improbability of the internet, to stumble upon just the right input at just the right time.

To set the scene: I finished watercoloring my hourly comics tonight, and have been thinking a great deal about repetition and sameness and grief and depicting the people and places you love. I’ve also been picking apart why, having made this intimate portrait of what it looks like to care for my aging father day in and day out, I feel more comfortable with the idea of sharing the comic online with an audience of thousands than I do showing it to my own mother.

Tonight, the knack looked like going on Twitter to follow someone I’d just met through a private Slack, reading the last few tweets in her timeline, seeing a link she’d posted in early 2021 to a now-archived blog, clicking through and laughing at the blog and then feeling like the curator‘s name was familiar, realizing I’d read a book she’d cowritten some years ago, perusing a list of essays on her website, and finally clicking on the first one because it was about “death, mourning, the artist Pierre Bonnard, and how to make a vital life out of repetitions and sameness, rather than newness and adventure.”

Here she comes:

There is a deep, dark, endless feeling to representing one’s insides. What appears in your writing changes the objects and people around you; they take on the qualities of how you portrayed them. A friend drawn ugly becomes ugly. A life drawn sweet becomes more sweet. To draw your life is to attempt to transform it with your magic. Your life invariably comes to resemble the depiction layered on top of it, because you now look at it through the lens of how you depicted it. This is why some artists run away from their lives; because who among us can live forever in our own dream?

I threw that bold in there, because that was the point I sat up straight and thought “OH SHIT.”

Of Bonnard’s working method the curator Dita Amory wrote, “Only when he felt a deep familiarity with his subject—be it a human model or a modest household jug—did he feel ready to paint it…. Asked if he might consider adding a specific object to his carefully circumscribed still-life repertoire, he demurred, saying, ‘I haven’t lived with that long enough to paint it.’”

I have repeated that phrase in my mind so often since encountering it, twisting it this way and that: I haven’t lived with it long enough to paint it. I haven’t lived with it long enough to write about it. I haven’t lived with it long enough to love it. What does it mean to distrust the novelty of experience? To say instead that what one needs in order to create are not new things—not new grand adventures, not new wives or husbands or cities—but the same thing over and over again until a Platonic form of the thing builds up in the mind and becomes the model for what is written about, or painted?

There were many moments in the course of penciling and inking my hourlies that I found myself drawing things without reference and feeling surprised—as if I haven’t interacted with them daily my entire life. As if I haven’t seen the exact pattern of my father’s behaviors day in and day out for an entire year.

I keep thinking about fixed action patterns in animals.

I keep thinking about what is being cemented in me during this season.

We all know that there is a quality of duration that must be harnessed, which seems to be not only a way of working against the fickle intrusion of inspiration but the only way of living after a certain age: understanding the humdrum repetitions of life to be a kind of balance; refusing to chase the tsunami of inspiration that comes with each new falling in love, each new city; having only the same walls around us, and the same plates, and only one wife, who will always dislike our friends, and spend day after day in the bath.

(I even have a wife who loves the bath! It’s not relevant to the main thrust of this, but I do love my wife and my wife loves the bath.)

There it is: the delight of finding something that speaks so precisely to the moment I’m in—down to the second. And then the wondering about whether reading it on any other day would’ve left me cold.

(The first time I read Ali Smith I bounced off her work entirely. And now I’m reading everything of hers I can get my hands on.)

Walking in the forest with my dog a few weeks after my father died, I noticed the green of the fir trees; the colors were so muted and beautiful. And up above was a flat gray sky, easy to look at, the sun dimmed at midday by a thick layer of clouds. All I could see were the colors in nature and their perfect harmony. I could have stood there staring for much longer if my dog hadn’t been impatient, and if my shoes hadn’t been wet. Everything was dripping, the previous day’s snow already melting. And because I felt in that moment as if I had never really looked at colors before, I stood wondering beneath the shadowless sky whether, when my father died, the spirit that had enlivened him passed into me, for I had held him as he died; as perhaps when his father, a painter, died, his spirit went into my father, so that now I had the spirit of my father and the spirit of my grandfather both inside me. And I wondered whether this influence—the spirit of my painter grandfather inside me—was why I was suddenly noticing colors.

What a gift.

New year, new Ramble.

This one (my 30th since I started this practice in June of 2019!) is about stuff I lost track of in 2021, things I’m thinking about in the new year, trying to abandon perfectionism, what to share and what not to share, the topography of the Ojai Valley, and various other things.

Also: looked at a bunny, found some owls.

You can read the transcript or browse all the notes and associated ephemera over on Patreon for free, or just listen directly below.

[Rambles are typically 20-minute freeform audio updates recorded outside every couple of weeks. You can listen to previous Rambles here or subscribe directly in the podcast app of your choosing with this link.]

I’m an inveterate thrower of clothes on the ground at the end of a long day. Always have been. If I’ve gotten sweaty or messy enough to huck them straight into the hamper, great, I can do that. But the truth is I usually wear things more than once before putting them in the wash, and so I throw them on the ground instead.

All days have felt like long days lately. This means I find myself wading through more and more mess as the weeks drag on, until I have to dig myself out over the weekend and return to some form of sanity.

Living in Portland it used to be easier. Or rather, I had a lot more floor space to fill up before things became untenable. But now I’ve moved my expansive Portland life back into to my childhood bedroom and there is very little wiggle room in either floor space or desk space. Things devolve from “slightly untidy” to “Death Star Trash Compactor” in very short order.

A couple weeks ago, when I found myself preparing to cast yet another t-shirt onto the ground in the desperate rush to get flat, I stopped. For no apparent reason, I thought about how putting the shirt away would be a kindness to Future Lucy. A gift.

I found myself thinking: “I want to care for this person.”

I wonder if this has something to do with becoming a caregiver for my dad. So many nights I find myself exhausted and ready to be unconscious, but I rally to do physical therapy with him, or make his smoothie for the following morning, because I love him and want him to be healthy and cared for, and also because he isn’t able to do those things for himself.

There’s a certain amount of distance I need in order to extend compassion to myself. Future Lucy isn’t here. She’s hanging around tomorrow morning, readying herself to face the day. I want to make it easier for her.

So I’ve started putting shirts away—although not without a certain degree of attitude. Usually I am muttering to myself, but I’m muttering about how this is a gift, and that it’s one I want to give because I love the version of me who’ll show up and do all of this all over again tomorrow.

It works.

I am wired for coming home in the same way it is assumed we are wired for leaving. Any adventure that lures me out is no match for the ties that draw me home again. I come home in the way you’d fall asleep after a day spent in the heat of the sun—before you know it’s happened, before you know you want to. Half the pang of growing up for me was realizing that I’d somehow have to create a sense of home wherever I went, that for all the effort I spent trying to leave, all I would ever want to do is figure out homecomings, ways of returning to the place where I feel the most like me.

Libby sent me this Rainesford Stauffer essay from The Atlantic (adapted from her book An Ordinary Age) and god damn. It’s about home and motion and FOMO and belonging and it is very, very good.

Where do you feel safe, and like you belong? Are you homesick for many places, like a hometown and a college town and maybe somewhere entirely different? Is it possible to have roots in multiple places?

The last one: woof.

I spent so much of my childhood wrestling with confusion over where I was supposed to fit in. English parents, California upbringing. Older family, only child. House full of books and in-jokes and accents and cultural references my peers didn’t get. A voice that sounded out of place on family visits to the UK. I wanted so badly to figure out why it was so hard for me to feel a sense of belonging, or why, when I did find a place that seemed to capture the rare scent of home, I couldn’t quite fit in.

It’s a much longer conversation than I have time to dive into now, but that question—the notion of being homesick for many places—just knocked the wind out of me. I stopped wrestling with it quite as much as I got older—partly because I began to grow more comfortable with myself, but also because I started to feel shame around wanting to explore immigration or dual nationality or being a third culture kid when a) my nationality is split between two massively privileged, problematic countries, and b) I’m white.

I know it’s not that binary. I’ve had rich, magical conversations with friends from varied nationalities who have enunciated things I never thought I’d hear another person capture. We’ve found common ground in those moments and it has felt like a form of belonging—of home. But I’m still scared to claim it. The focus at this moment in time (rightly so) is on making space for the intersections of identity that have been elided or repressed by White Supremacist culture to be heard. I don’t feel like I have the right to take up space with my own investigation into why I feel out of place—at least not in public. I know, on some level, I am robbing myself by doing this, but I’m still trying to find my way toward the method that feels both ethically considerate and true.

Anyway, the Stauffer essay. It was very good.

…of somewhere I’ve been coming for a long, long time.

It turns out you can counteract a lot of “I Work on a Computer All Day” angst with nothing more than a pair of branch loppers and an hour on an overgrown hillside trail.

I’m pulling into Santa Barbara, 940 miles of highway behind me, as the sun dips low to the west. On my right: occasional glimpses of the sea, tantalizing and unreal, but ahead there’s only bumper-to-bumper traffic.

I’m racing the clock as I inch through Montecito, drumming my fingers on the steering wheel. The sun’s fully below the horizon by the time the cars thin out, but there’s still time. I’m navigating by instinct across overpasses and down twisty back roads. I’m ignoring the sign that says “Park Closes at 5:30” (it is after 6) and flinging my car across two spaces in my haste to get out. I’m scrambling toward this place I’ve been coming to since I was 3 because I am giddy with disbelief and this is where I need to go to know it’s real.

James calls right as I reach the edge of the sandstone cliff. The sea is mirror-bright and full of sunset. I show him my view (an inadequate FaceTime mockery) and babble about the impossibility of it all. The prickly scrub is catching at my ankles as I stare out at this thing I’ve been unable to feel like I deserve to be near for so long. I realize there’s no time for talking, make my apologies, hang up, and start running down the slanted track to the sand.

There’s barely anyone on the beach as I kick off my shoes. The light’s failing. Everything smells of salt and woodsmoke.

Up close, the colors in the sky and the immensity of the water make me dizzy. I feel simultaneously tiny and expansive. Opening. Unfolding.

What’s the rule?

If I am near a body of water and I can feasibly get into it, I must get into it.

I didn’t think to grab my towel—or my bathing suit, for that matter—but I don’t really care. There isn’t time. I strip to my underwear as the dark closes in and stride toward the water. The sand is gleaming blue with light. The waves are gentle at first, waist high and cold, but I’ve braved worse. I can’t believe I’m here. I shuffle my feet, wary of stingrays, and move deeper, chattering to myself. To the water. To the sunset.

“Hello. Wow. Hi, hello. Oh my god. Hello. I missed you. Okay. Woof. Okay. Okay okay okay here we go. Here we FUCKING GO—“

And then I am under the onrushing breakers and nothing matters anymore. I am not cold. I am not alone. I am not uncertain.

I come up laughing, and I am home.