I stopped off to download my Twitter data yesterday and caught a notification from this lovely thread that Brendan had put together sometime around Christmas:

Down among the thinkers and tinkerers and connectors, said the notification, he’d written some very sweet things about me. It came as something of a surprise.

It was a mention of “unselfing” by Helen Macdonald that drove me back to blogging in 2020. Since then I’ve heard it surface in other places. Annie Dillard describes it at length in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, saying “[…] I have often noticed that even a few minutes of this self-forgetfulness is tremendously invigorating. I often wonder if we do not waste most of our energy just by spending every waking minute saying hello to ourselves.”

Both women have their fingers tangled up in something true.

I feel it when I’m driving the highway, lost in dark thoughts of mortality, only to abandon every thread for a glimpse of a hawk on a telephone pole. The moments before sleep when a barn owl’s screech pulls me out of my own body. The day I left the house in a foul mood to pace the gravel drive, stomping up and down until the lifeless body of a hummingbird stopped me short and lifted the needle of my displeasure.

I know the value of unselfing more than I ever have before, living here, doing this work, marinading in the near-depth of near-death.

But this thing that Brendan gave me feels somehow the same—an inverted twin sensation: being reminded out of the blue of Who You Are (or Were) Perceived to Be. It comes to me in a season where I’ve stopped saying hello to myself quite so often, possibly to the point of forgetting who that self even was before now. I say hello to death, I say hello to loss and calibration and labor and tending, but I don’t always say hello to me.

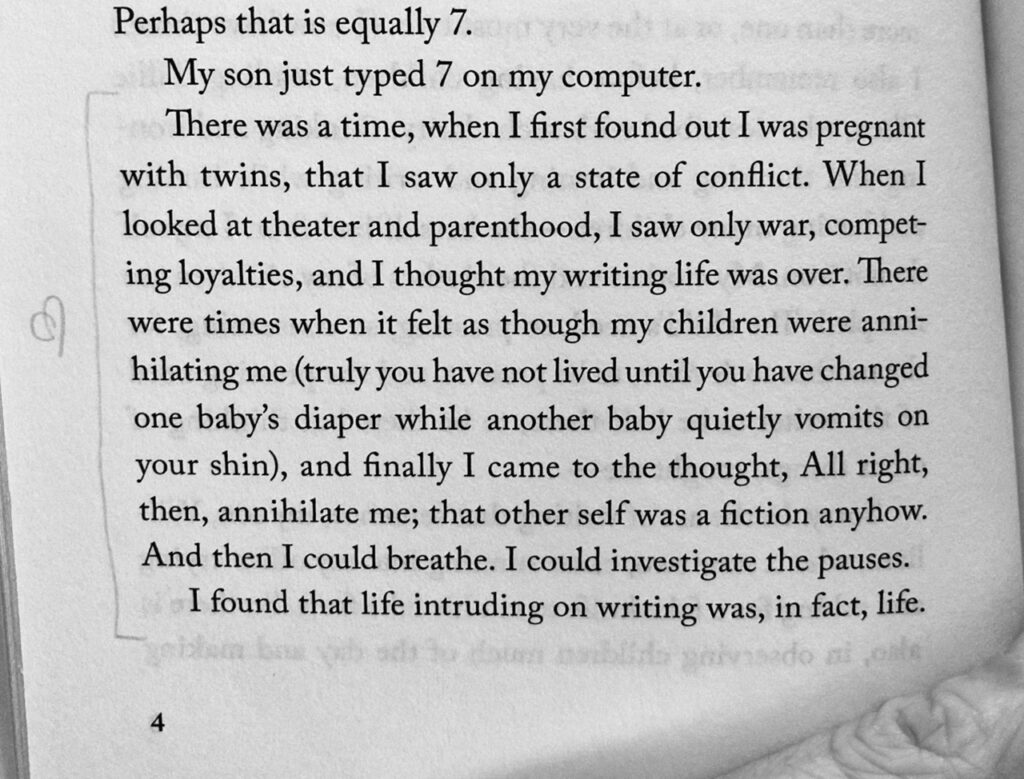

And the minute I type that I’m thinking of Sarah Ruhl, and these lines from the first essay in her book 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write:

I’ve written about that line here before, and the mantra repeats in my head as I walk through the meadows near my house.

All right, then, annihilate me; that other self was a fiction anyhow.

All right, then, annihilate me; that other self was a fiction anyhow.

All right, then, annihilate me; that other self was a fiction anyhow.

And yet, and yet, and yet…

I miss her. I miss that Lucy. And so Brendan’s tweet feels like a kindness. Perhaps the kindness that social media kept drawing me back in with for all those years: a whole realm of people who could look at every passing thought and doodle and hard-won victory and low moment and interview and blog post and reflect back someone cohesive and true.

True only to what I’d shared, maybe, but still.

Something I couldn’t see with my own eyes.

Something the hawk sees when it’s looking back at me.