What’s the thought you think all your life long? It must be a great one, a solemn one, to make you gaze through the world at it, all your life long. When you have to look aside from it your eyes roll, you bellow in anger, anxious to return to it, steadily to gaze at it, think it all your life long.

— To The Bullock Roseroot, an improvisation spoken during the Second Day of the World ceremonies by Kulkunna of Chukulmas

I’ve been making my way, very slowly and over the course of many loans from the Multnomah County Library, through Always Coming Home, Ursula K. Le Guin’s unclassifiable, meandering, pseudo-anthropological record of a fictional future people called the Kesh. I’m not even a third of the way into the thing, but as the above quote from the book suggests, I’m thinking about it all the time.

There are so many things I love about this collection, particularly its place-specific-ness. The Kesh live in a far-future, post-societal-collapse Northern California. Even with the ravages of climate change, they describe the local flora and fauna in a way that taps straight into the landscape of my childhood—what Cassie Marketos calls “our good earth to grow in”. It brings me back to hot, dusty hikes through the Sespe wilderness in grade school, shifting my weight side to side as a leathery naturalist lectured us on different varieties of manzanita. It roots me in a place I think about even when I am not thinking about it.

⚘

If we are friends in any capacity, chances are high that I’ve pressed Le Guin’s essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” into your hands at one point or another. It explores a hypothetical world where stories are about the things they gather and contain, rather than the bodies they pierce and conquer, and I want to talk about it with everyone. It took me years to bother looking up where it had originally been published, which led me to Always Coming Home. Now that I’m a third of the way into this massive, discursive, lovely collection, it makes perfect sense. Theory in practice.

⚘

I like a book that forces me to take my time.

⚘

I’m a fast reader, and the first to admit that I can get a little breathless with my consumption. I spin out over ideas, get caught up in the excitement of newness. A book like this resists every opportunity to rush. The chapters and sections are all relatively small, but they loop and meander and digress. They build in layers over hundreds of pages to give an impression rather than a narrative. The experience feels very similar to reading oral traditions of cultures other than my own—an abruptness as one’s expectations of narrative symmetry and pacing are undermined in real time. The lack of them speaks louder than anything; makes me more aware of what I’ve been raised with, and of how things could be different.

⚘

Despite their distance from our current world of technology, the Kesh still interface with certain vestiges of present-day culture. These moments are some of my favorite in the book so far.

The City mind thinks that sense has been made if a writing is read, if a message is transmitted, but we don’t think that way. In any case, to learn a great deal about those people would be to cry in the ocean; whereas using their bricks in one of our buildings is satisfying to the mind. […] What does it mean to cry in the ocean? Oh, well, you know, to add something where nothing’s needed, or where so much is needed that it’s no use even trying, so you just sit down and cry.

If that isn’t social media in a nutshell, I don’t know what is. The desire to know everything, consume everything, document everything butting up against Marge Piercy’s recognition:

Greek amphoras for wine or oil,

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums

but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry

and a person for work that is real.

When I retweet or double tap on a post by a friend to express my approval, I’m not using their bricks in one of my buildings. But when I write? That’s when we’re in conversation—occupying the same room across space and time, building it together.

⚘

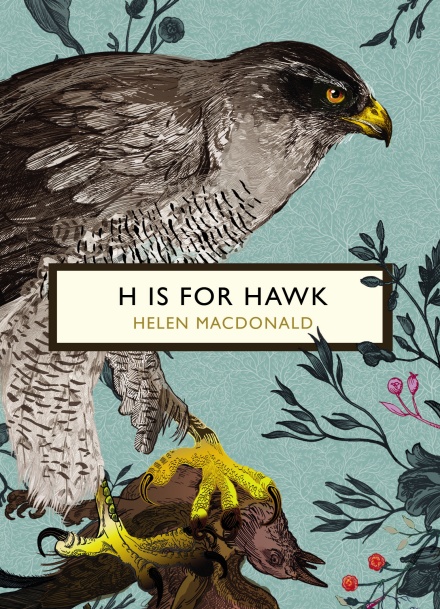

This is what Le Guin manages, in this layered, looping collection of stories and ideas: she writes a re-envisioned world into being, and then writes herself—writes all of us who create—into that world. “What do they do,” she asks, “the singers, tale-writers, dancers, painters, shapers, makers?”

They go there with empty hands, into the gap between. They come back with things in their hands. They go silent and come back with words, with tunes. They go into confusion and come back with patterns. […] The ordinary artists use patience, passion, skill, work and returning to work, judgment, proportion, intellect, purpose, indifference, obstinacy, delight in tools, delight, and with these as their way they approach the gap, the hub, approaching in circles, in gyres, like the buzzard, looking down, watching, like the coyote, watching. They look to the center, they turn on the center, they describe the center, though they cannot live there.

It’s the doubled items in this list that I love the most: “work and returning to work,” “delight in tools, delight”. I love that Le Guin understands these as separate, yet interlocking elements. I love that she has thought, so deeply and with so much lenience and also so much slantwise clarity, about the purposes we might serve in remaking the fabric of society.

She was a writer with a thought to think her whole life long. And the beautiful thing about writing is that the thought didn’t end when she did—now I’m thinking it, too.