Back at the start of March I uncovered this cookbook in our overstuffed kitchen shelf. It’s incredibly upsetting, even for something designed in the 60s.

NOBODY WANTS THAT ON A BOOK ABOUT FOOD.

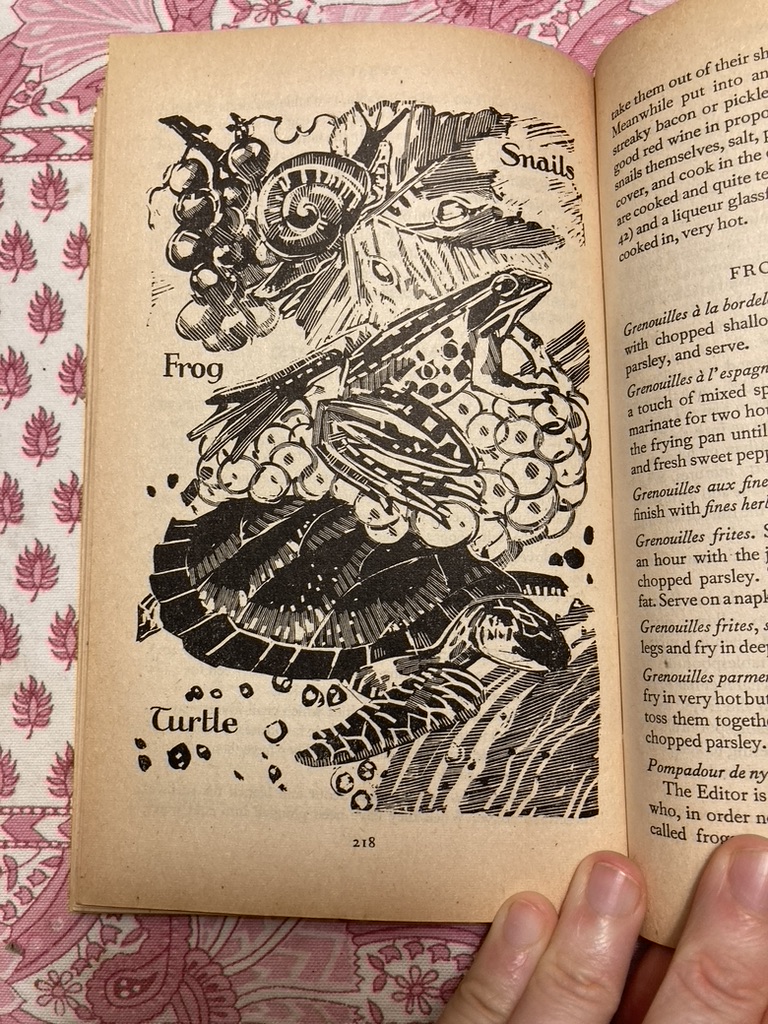

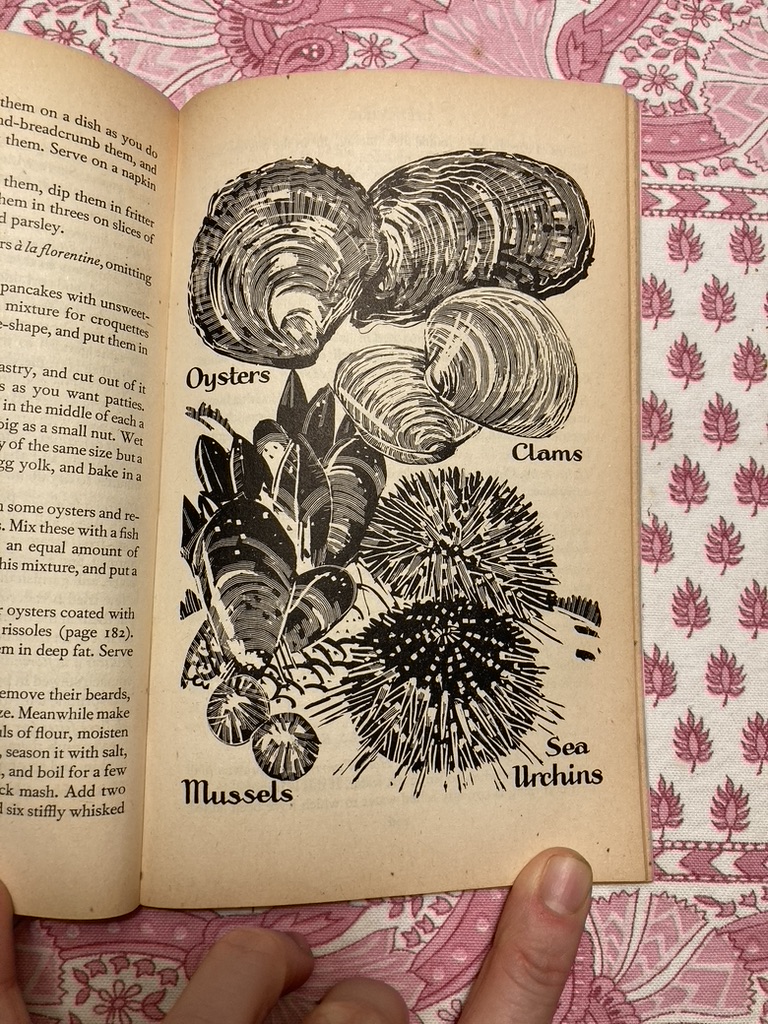

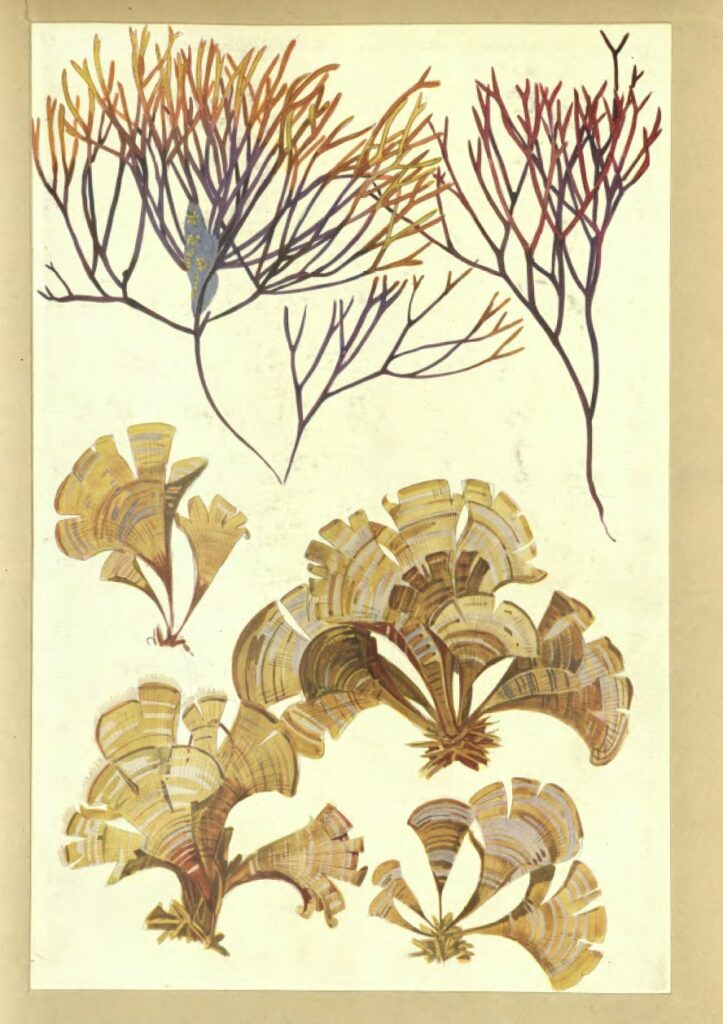

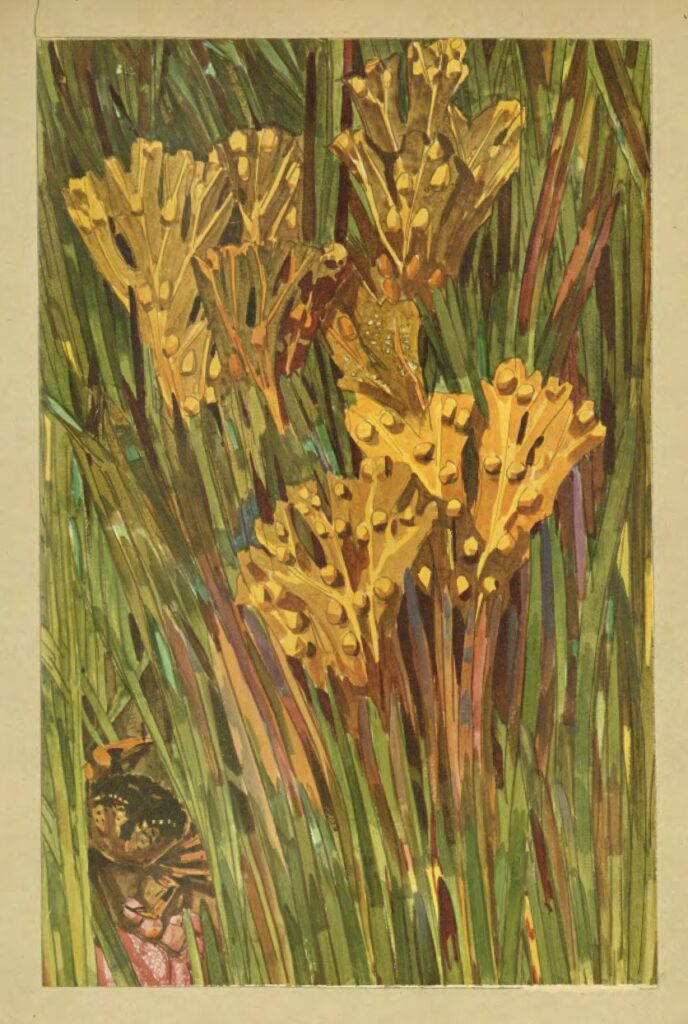

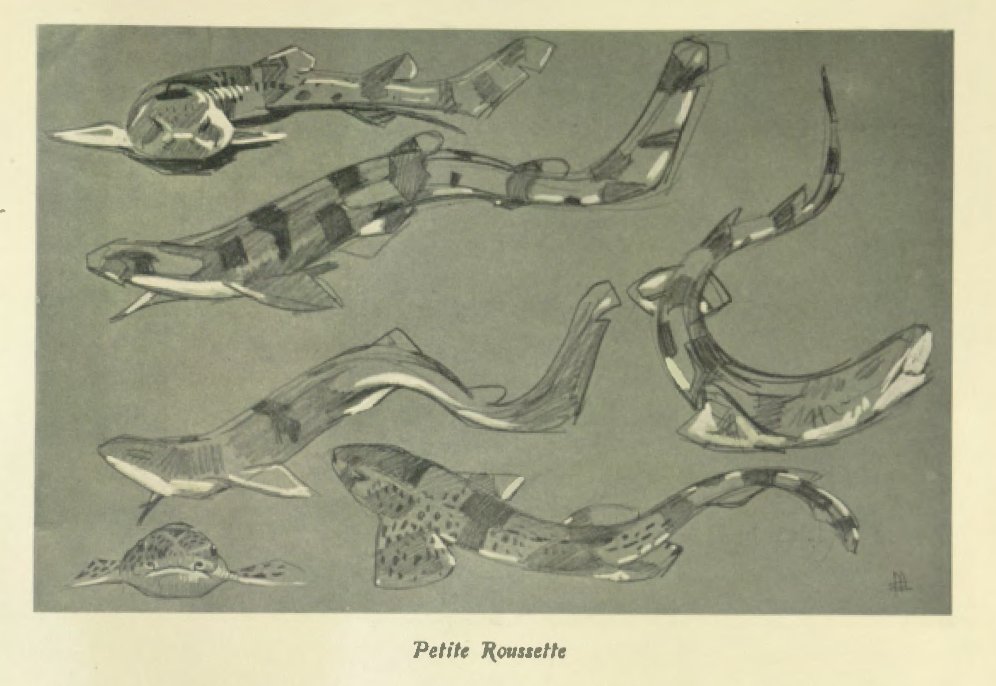

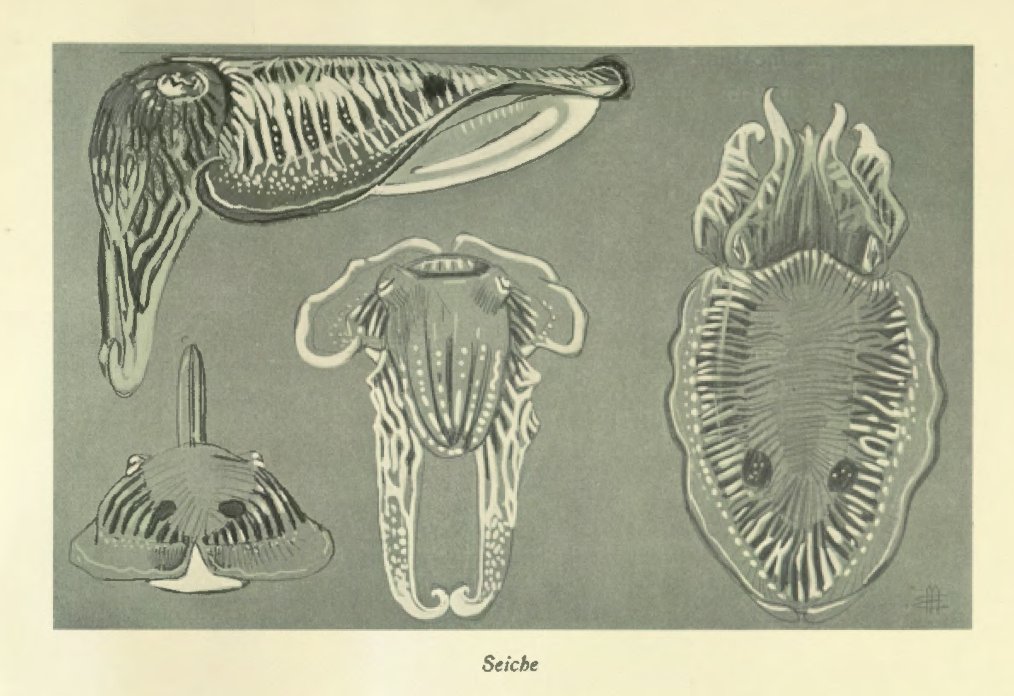

But the original text, I should mention, is from 1939. And when I cracked it open I was surprised to find that the illustrations were incredibly cool.

Look at those lines! So stylized! So energetic! And the compositions!

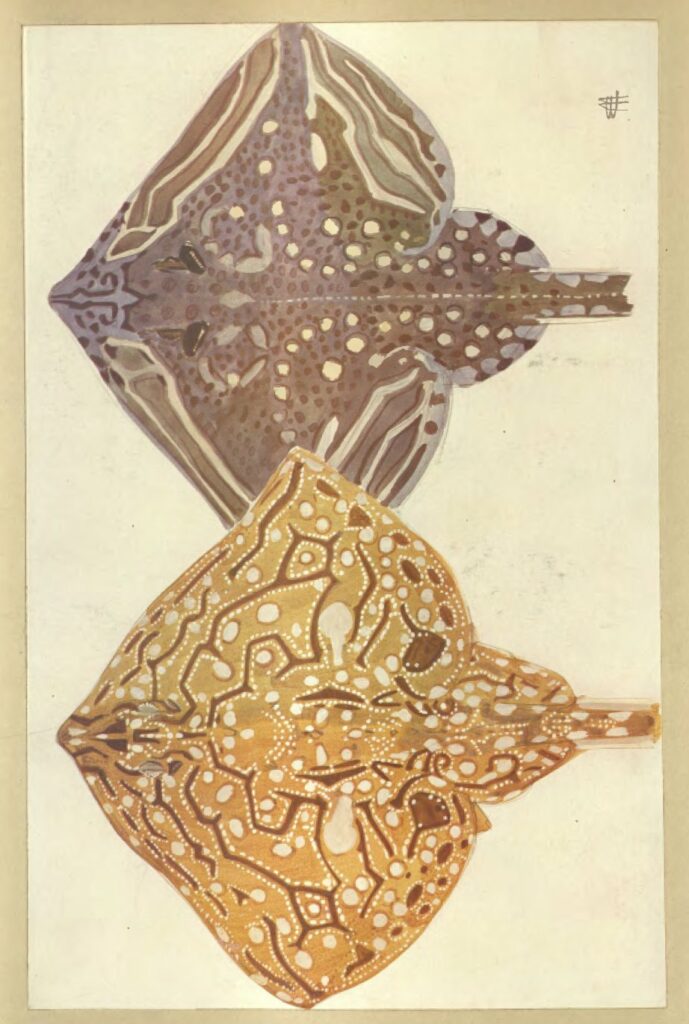

Turns out the interior artist is one Mathurin Méheut (1882-1958), a French painter I’d never heard of before. When I went searching for more of his work, I found a treasure trove. Méheut had spent two years before WWI working with naturalists at the Roscoff marine biology station—a collaboration that resulted in two enormous volumes of gorgeously-depicted marine life.

And, to my immeasurable delight, both of them are available online via RISD’s library.

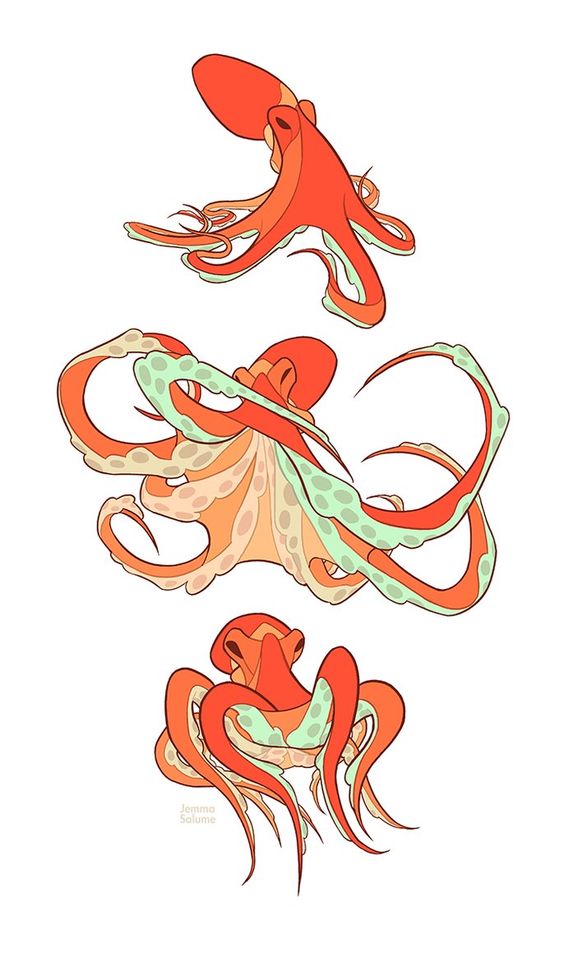

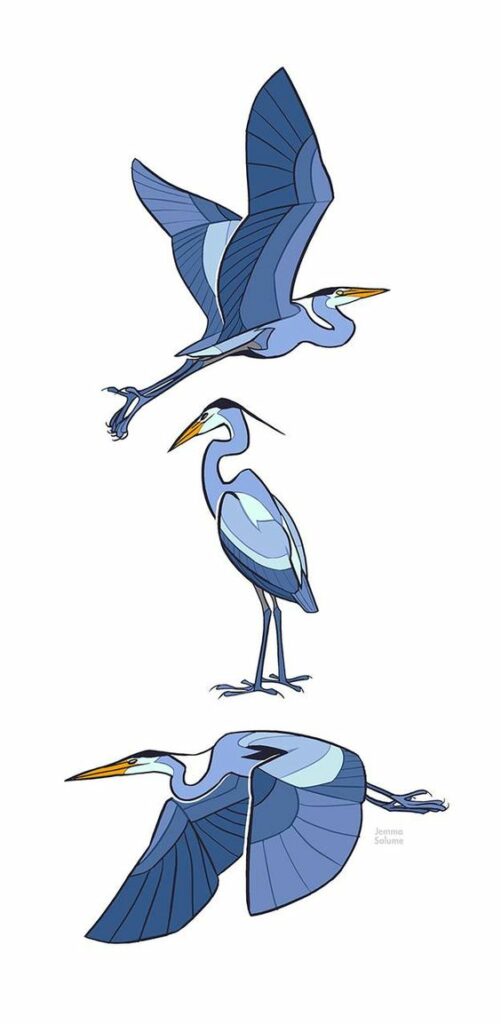

I love stumbling on illustrative work like this. It feels so modern! There’s a level of stylization that really reminds me of Jemma Salume’s animal studies.

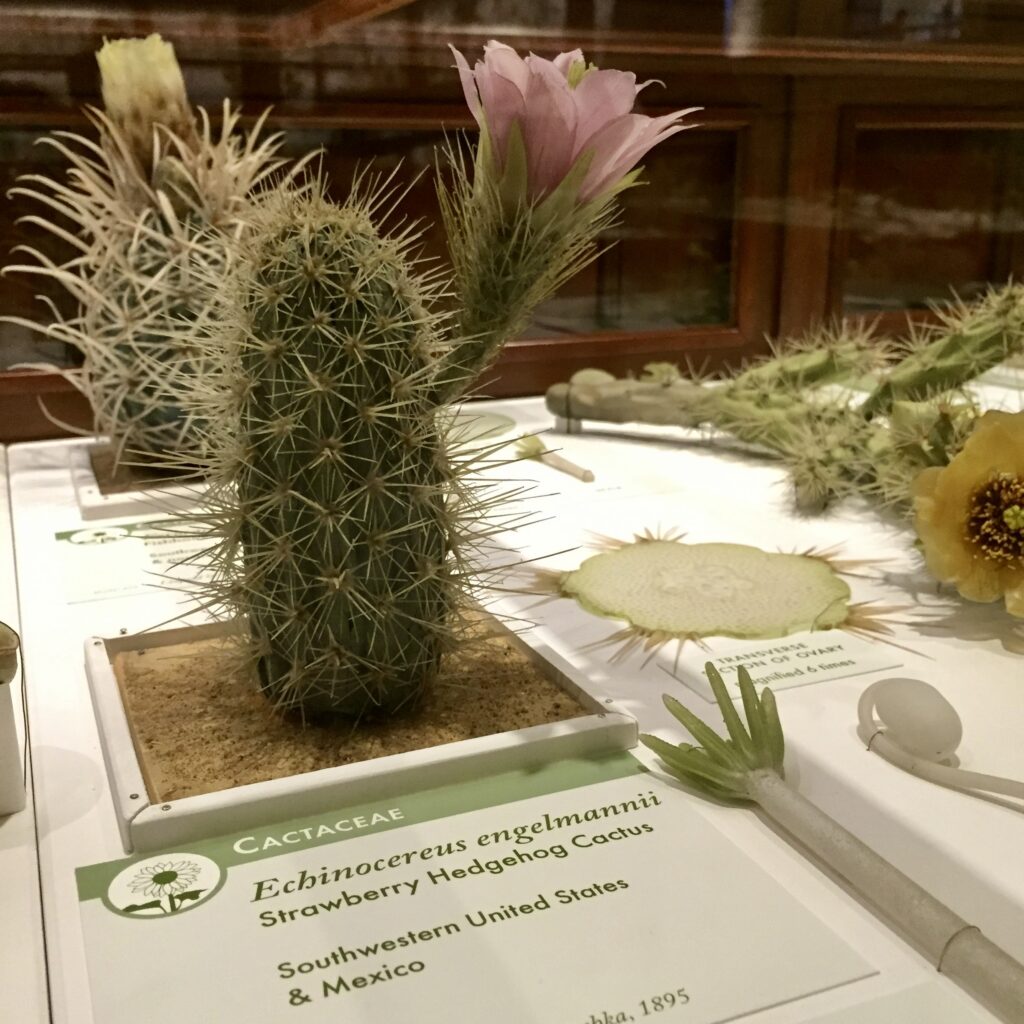

I also can’t help thinking about the work of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, the father-son team known for creating the most exquisite glass models in human history. Their success lay in capturing the shapes and colors of marine invertebrates at a time when methods of preservation typically left specimens looking like so much indistinguishable mucus.

This octopus? GLASS.

This cactus? ALSO GLASS.

Unreal. (And well worth a visit if you ever find yourself near the Harvard Museum of Natural History.)

In the process of writing this post, I learned that Leopold fell in love with marine invertebrates in 1853, when the ship carrying him to America was becalmed for two weeks near the Azores. His wife and his father had just died within a few years of each other. The trip was something of an escape.

I think about him, adrift and grieving in the middle of the ocean, with nothing to do but stand on deck in the night and pay attention.

Hopeful, we look out over the darkness of the sea, which is as smooth as a mirror; there emerges all around in various places a flashlike bundle of light beams, as if it is surrounded by thousands of sparks, that form true bundles of fire and of other bright lighting spots, and the seemingly mirrored stars.

✵

Little wonders all around.