I’m wrestling with the letter I want to write to introduce my 2020 100 Day Project when I release it later this month. I’m feeling the pressure to get it just right. To say it just so. (Sound familiar? I keep finding different elements of this project to obsess over as a way to avoid sharing it. Go figure. Just share it, Lucy.)

I poked my head into Instagram briefly this morning and found Anis sharing a project that has its roots in a much older project and is now reemerging:

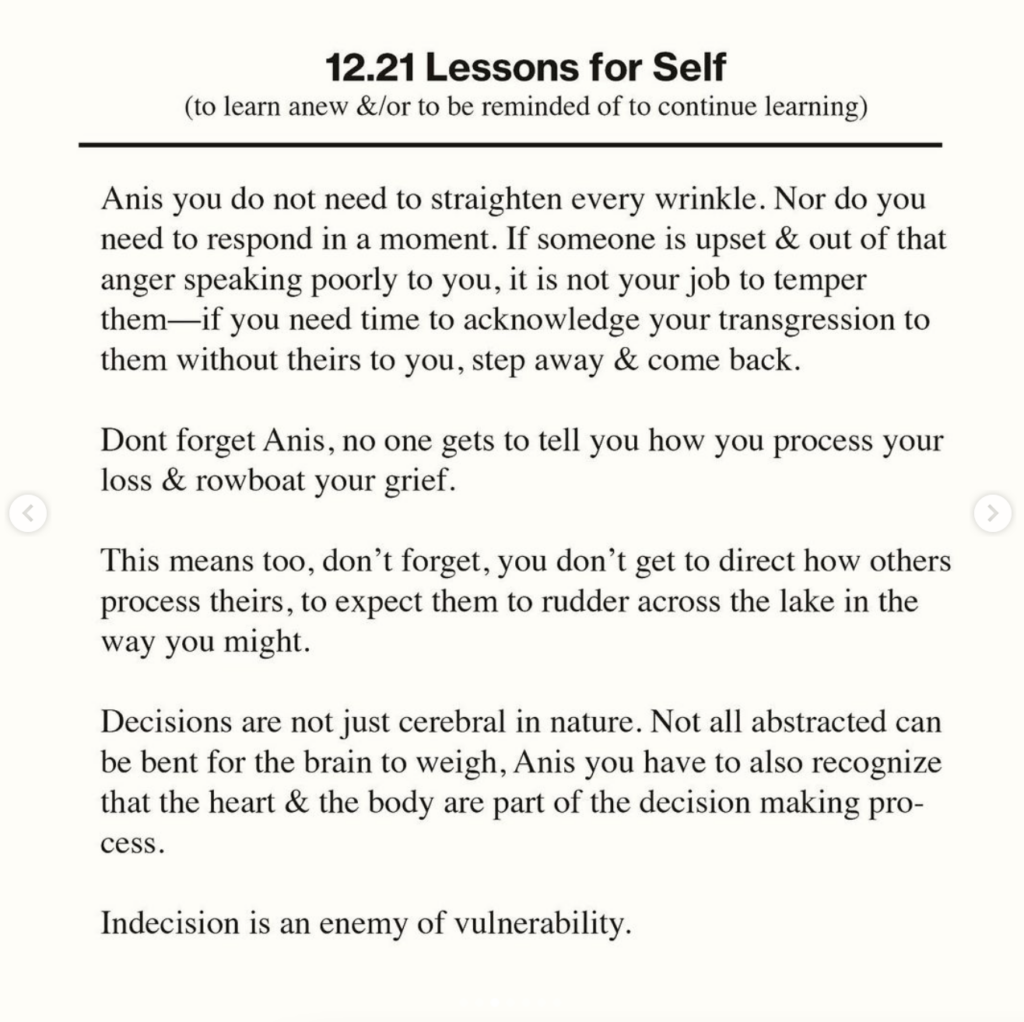

Back in 2014/2015 I was in a place of heavy loss, a place of relearning, rewiring, reforming my self, & began writing down & sharing online these monthly wisdoms/lessons for my self to learn, think on, & try to remember. Have wanted to return to this for years now, & being now in some months of heavy reflection seemed a good time for this returning. Here’s things I put down last month for me to hold & turn over & try to remember.

Here’s one:

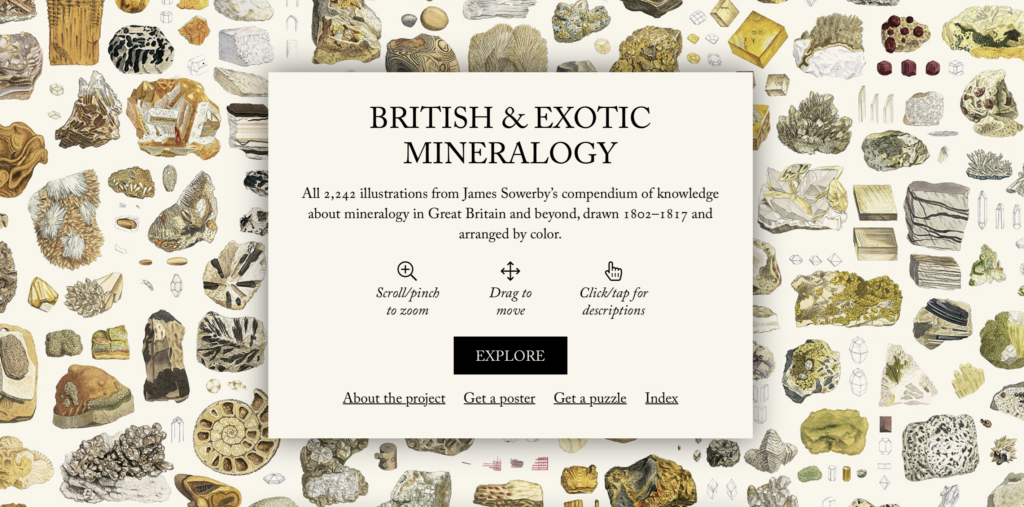

This subtitle sings to me.

It’s a funny thing how we all begin turning toward the same subjects at the same times (or have already been turning for several years). Reminders. Permission. Speaking to the self as the self, but at a removal from the self. This is the energy of the thing I’m about to release, too. Seeing it reflected in these words from my brilliant friend fills me with compassion and energy and, okay, a little envy, too. I have to elbow myself in the psychic ribs as if to say “Hey. Cut it out. There’s no race here, ya dingbat.”

On another slide, Anis writes:

I sometimes use vulnerability w/self to avoid vulnerability w/others. I wear my heart, but wearing can be a costume.

This is one of the things that drives me away from sharing such a personal thing in public. I want it to be known (I want to be known), but not in a space where I’ve traditionally used perceived vulnerability to mask real connection.

The greatest pleasure I’ve gotten from this project has been pressing the physical prototype (or the Dropbox folder of images) into the hands of trusted friends, and then talking about it with them. That’s energy I want to preserve moving forward. This connection. This depth.