I originally published this essay on Medium in 2019. I’m reposting it here on my site because a) I want it to live in an online space I own, and b) it’s still infuriatingly relevant. With the Supreme Court continuing to threaten Roe v. Wade in the United States, it feels vital to normalize and humanize the wide variety of narratives around abortion. The National Network of Abortion Providers maintains a directory of local funds here. The Guttmacher Institute also has a map of states likely to ban abortion if the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, which makes a decent cross-reference for where to direct funds if your state isn’t likely to implement a ban.

I also want to note that this issue impacts anyone with the reproductive capacity to become pregnant, including trans, intersex, and nonbinary people. (The Guttmacher Institute only began including explicit questions about these groups in their 2017 survey.) This isn’t just about “women’s rights”. I’m still working on expanding my understanding along these axes, which I share here in case anyone else is doing this same and feeling adrift. We’re all learning. Let’s keep learning.

CW: This essay deals with the emotional fallout of having an abortion as a teenager. You’ll see no shade from me if that’s not something you’re able to read about right now, but if you do manage it: I’m grateful.

I am sixteen, sitting sun-warmed against the stucco wall of the school library, hearing my voice shake as I schedule an appointment at Planned Parenthood. I am six weeks pregnant and scared out of my mind.

The nurse is very calm, explaining slowly and clearly what I should expect. We set a date during the week of my school’s spring backpacking trip. The morning I’m supposed to leave for the desert I call the trip leader and feign illness, but I’m not really lying. I am nauseous. Me, the kid who never plays hooky for anything, skipping a trip I’ve been looking forward to for months in order to have an abortion.

My pregnancy is not the product of an assault. It is just a mistake. I am young and ill-informed and, after seeing the results of the at-home test I smuggle into my family’s bathroom, floating ten feet above my own body in a state of absent horror.

But I am also lucky. My parents are shocked, but sympathetic and supportive. My state supports safe and legal access to reproductive care. I have been working as a lighting designer to save money after school. We all pitch in to pay for the procedure.

I throw up on the way to the clinic, unable to tell if it’s morning sickness or self-recrimination that drives me to hang my head out the car door and gag into the dirt. I think I am a monstrosity. A pariah. Even growing up in a progressive hippie town, my inherited societal commentator tells me I have made an unconscionable mistake, and now the only way to deal with it is an unconscionable choice that will haunt me forever.

Except it does not. Not in the way I think.

The staff are kind and gentle. The procedure goes smoothly. I keep tensing, waiting for guilt and remorse to follow the physical discomfort, but they do not come. After the sickening anxiety of the previous ten days, the whole experience grants me a sense of relief that doesn’t add up to what I’ve been told I should feel. The abortion is not the thing that damns me; it is the thing that absolves me. I have been given a chance to be more intentional — to carry my own dreams a little longer before choosing whether I will make them a scaffold for another human being.

I find hormonal birth control that works for my body. I go on to travel the world and graduate from college and build a career that nourishes me in so many ways. As I get older, I don’t avoid talking about the abortion per se, but it doesn’t come up very often in conversation.

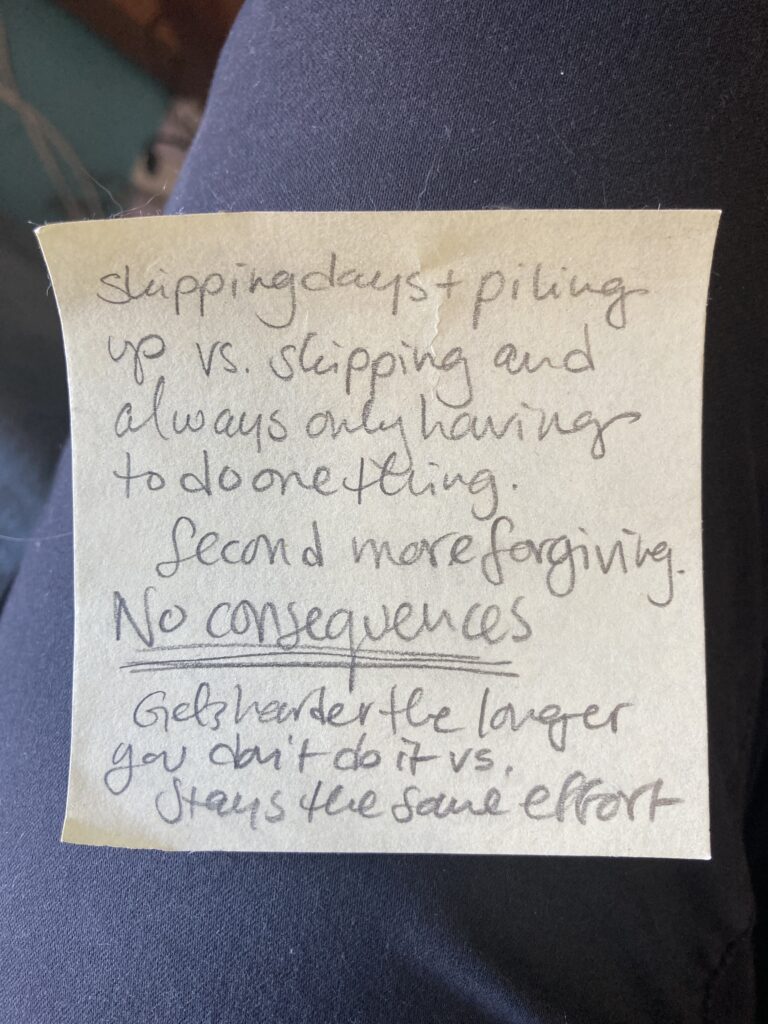

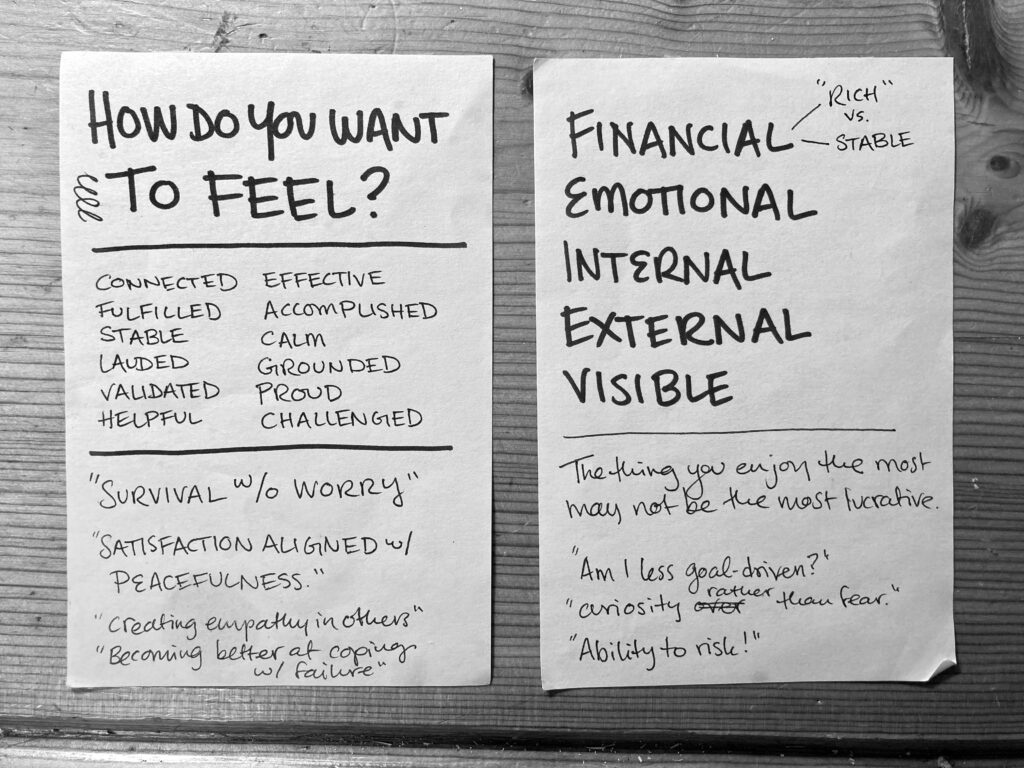

Somewhere along the line I realize that I’m not discussing it because it feels unjustifiable. My life was not at risk. It would have been hard, but it would not have been impossible. I struggle with the belief that I was less worthy of access to this choice because there were no extenuating circumstances.

The discourse continues to escalate. People write op-eds. They launch hashtags. They share stories. They take to the streets. At every turn I consider joining the chorus, but I have seen that anyone wanting to make their own decisions about their body has to defend their right to do so in front of an angry mob, so I keep my mouth shut because “I didn’t want to” and “I wasn’t ready” do not feel like good enough reasons.

In 2017 I pass a man at the Women’s March in Honolulu holding a “Her Body, Her Choice” sign and break down sobbing. I realize some part of me still believes I do not deserve the life I’ve lived as a result of that procedure.

That same year, the Guttmacher Institute releases a study citing that one in four women will have had an abortion by the age of 45.

One in four.

I could have used this information back in 2007, trapped in that bell jar of shame. I could have known I was normal. It would not have killed me to carry that child, but it wasn’t the right time.

The conversations we’re having right now, however challenging and painful, are bridging the islands where we sit, isolated and hurt, thinking we are alone. Progress is not always a tidal wave of unified testimony. Sometimes it is quieter work, unlearning these messages in the deeper parts of ourselves — coming into the understanding of what is true for each of us, individually.

It would not have killed me to talk about this sooner, but it wasn’t the right time.

I think I’m ready now.