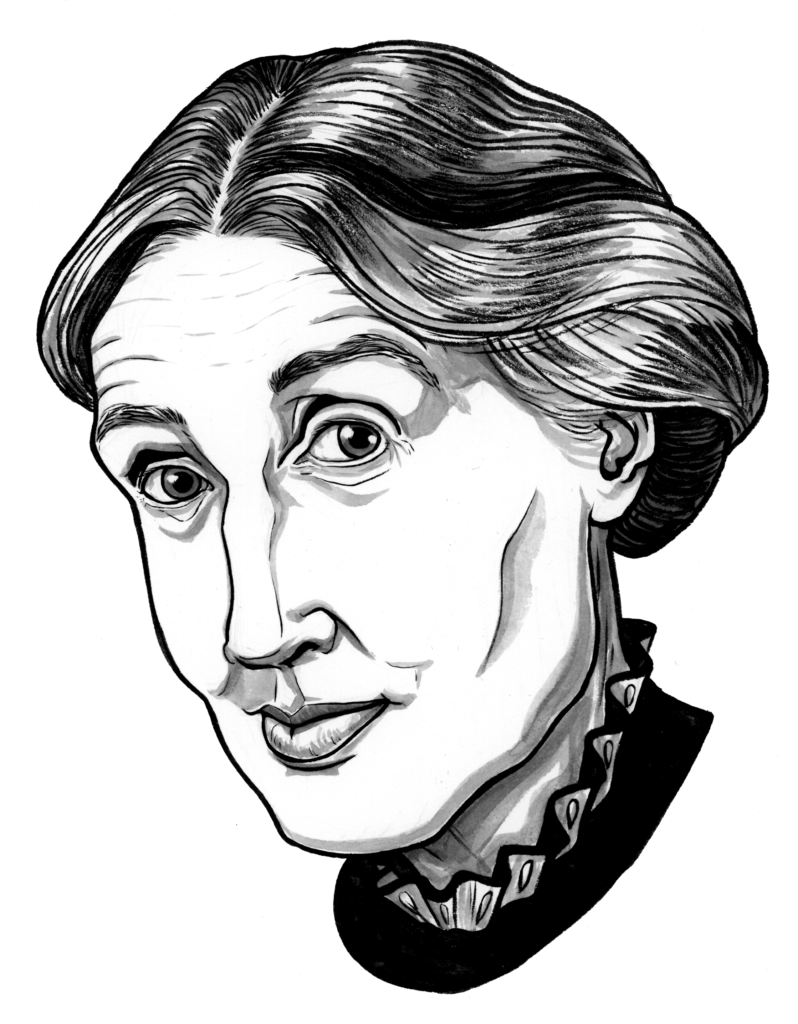

![A complex mind map connecting various names and creative works of nine people, mostly female writers.

The following themes are positioned throughout the page like nodes:

[See Me / Don’t See Me]

[Gardening]

[Queer Relationships]

[Utopia]

[Solitude]

[Fluidity]

[Rhythm]

Ursula K. (Kroeber) Le Guin 1929 - 2018

“The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction" 1988 in Women of Vision

2010: Began [Age 81] Blogging

No Time to Spare (pub. 2017, HMH)

A left-handed Commencement Address, 1983 Mills College

The Wave in The Mind (pub. 2004, Shambhala)

Epigraph: “As for the mot juste, you are quite wrong. Style is a very simple matter: it is all rhythm. Once you get that you can't use the wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting after half the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and can't dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it, and in writing (such is my present belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which has nothing apparently to do with words) and then as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it. But no doubt I shall think differently next year.” (Woolf to Sackville-West, 1926).

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941)

1931 Professions For Women

“It is a very strange thing that people will give you a motor car if you will tell them a story. It is a still stranger thing that there is nothing so delightful in the world as telling stories."

"The Angel in the house"

Orlando

The Waves

1929 Room of One’s Own

Met Sackville-West in 1922

Gail Godwin (b. 1937)

1977 (NYT) The Watcher at the Gates

12 Short Stories and Their Making (2005, Persea)

Appeared with Le Guin in same publication

“A story larger than my own” Working On An Ending, 2014

"Now I do a lot of lying around. I finally I have accepted that my supine dithering is fertile and far from a waste of time"

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) <-> Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962)

Nigel Nicolson (1917-2004)

Portrait Of A Marriage (1973)

Not to be confused with

Nigel Nicholson -> [Classics] [Reed College]

"The Bright Chimera" R. Rawdon Wilson

Olivia Laing (1977-)

Married Ian Patterson (1948) in 2018 [29 years apart!]

May Sarton (1912-1995)

(At Yaddo) "I hated all the shop talk. I'd rather see people who are carpenters, who are sailors or who work in healthy departments, because then I feel I am learning something about life."

“There is much less anguish and self-doubt. You are much more able to function freely, spontaneously, as yourself."

met Woolf in 1937](https://lucybellwood.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IMG_5457-scaled.jpeg)

The online home of Adventure Cartoonist Lucy Bellwood

“I thought by the time I was doing this I’d be with someone.”

I cried when I told her—another one of the myriad griefs threading through this kintsugi year: that not being in a romantic partnership somehow rendered me incapable of facing my father’s decline.

But when I was writing the FAQ about my move, I kept drafting and deleting a passage about how becoming single had actually given me the freedom to leave Portland.

Because it’s not true.

I mean, it is, but not the part about being single.

It’s Valentine’s Day as I’m writing this and I feel so far from being “single.”

“Most other people have a switch that gets flipped between friendship and relationship,” he used to say. “But you love people on a spectrum.”

I felt seen by that (he was good at making me feel seen), but there’s no decent shorthand for that kind of life. Or if there is, it’s couched in the culture of labels, and they’ve never done much good for me.

“Housemate,” for example, feels wholly inadequate for my relationship with Zina. We’ve lived together in one form or another for ten years; just the two of us for the last seven. The term we settled on at some point was Boston Wives, but that often involved giving an impromptu 19th century history lesson on female cohabitation to whoever was doing the asking. When we entered a Registered Domestic Partnership two years ago, I breathed a sigh of relief because I could just call her my wife and let everyone else muddle it out for themselves.

But what does that mean, really?

I’ve told people “Well, we’re not in a romantic relationship—” but then I stop. We take baths together and buy each other flowers and read epistolary science fiction love stories aloud in bed and fuck me if that isn’t romantic, I don’t know what is.

We turn to each other, in amongst all these activities, and say “We’re so rich.”

The older I get the more wobbly my definition of being “in a relationship” becomes. It sounds so singular.

I used to think I wasn’t very good at making friends. Being liked, sure, but not being vulnerable in the way truly reciprocal, intimate friendships demand. Never to ask, never to need. Far easier to unilaterally support other people to shore up my own sense of being worth something. Far better to fling all my devotion and intimacy into one heteronormative partnership and pin my hopes of making it through any major life challenges on that.

It’s a decent plan until it’s not.

Because I’m still going through this reckoning—relationship or no—and it’s forcing me to recognize that somewhere along the way I started figuring out how to be truly vulnerable. I picked up a community of (for lack of a better word) friends.

There are friends who bring me pie when my Kickstarter funds and soup when I’m down with the flu.

Friends I have flown across the country to support through unspeakable loss, who I know would do the same for me in a heartbeat.

Friends who are also lovers. Whose parents I have met. Whose kids I get to help look after when I visit.

Friends who will yell on the phone with me about books and websites at all hours of the day and night, pacing the block, gesticulating.

Friends who send nudes but also commiserating texts about caring for loved ones with dementia (a potent combo).

Friends who know how to reassure me of my intrinsic value when I think all I’m good for is being productive.

And these are the people in my immediate circle. Never mind the far-flung folks online, around the country—around the globe—with whom I have shared hotel rooms and letters and meals and Zoom calls. And then the circle beyond that: the strangers who have read my work and feel some degree of connection through that avenue. People I have never spoken to who might, given the invitation, share something heartfelt or helpful out of the blue.

I don’t know what to call all that, but when I stop to think about it I get dizzy and start to cry.

And beyond it lies the thing I hesitate to name because it feels trite: my relationship with myself. This person who delights me the more I get the measure of her, who has words of wisdom when I feel lost, who makes me laugh and brings me intellectual baubles and dazzles me with her tenacity and vision. I love my friendship with her most of all.

So here I am: not single, but communal. A dragon curled atop her glistening hoard.

Rich.

On April 16th, 2018, a friend of mine began a 100 Day Project—a collection of self portraits in ink, framed as a meditation on gender.

The tiny illustrations began to pile up: two weeks, 100 days, a year.

They kept drawing.

At 862, they stopped sharing to Instagram, but said they would probably keep going in private. (We love to see it.)

And then, a couple days ago, a text:

I asked how they were feeling about the milestone.

And now I’m laughing thinking about Benoit Blanc and donuts, because this is how I feel at moments like this—screenshotting a perfectly normal text conversation because something about it makes me think “HANG ON”.

Not the art, but the behavior around the art.

A donut! One central piece, and if it reveals itself the fog would lift, the arc would resolve, the slinky become unkinked…

It feels right, at least in relation to my own practice, which is often very much predicated on rules and rituals. (30 Days of Portraits. 100 Demon Dialogues. 1000 words a day.)

These are all projects where the structure of the undertaking supersedes the content. Fixating on the satisfaction of completing another link in the chain allows my less-than-perfect artistic skill to slip past the Watcher at the Gate undetected. Success is defined as adherence to the practice, not excellence in the craft.

The joke, of course, is that they’re one and the same.

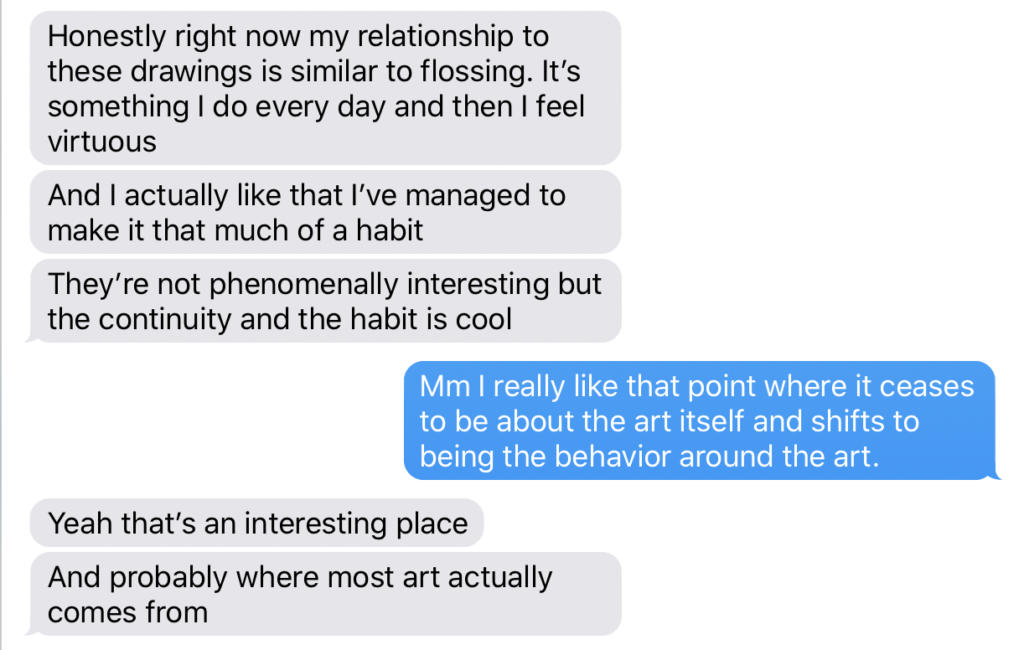

There’s a paragraph from Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit that lodged firmly in my brain when I first read it in college. (I loaned my copy of the book to a friend years ago and it was only recently returned it to me, so this is the first chance I’ve had to go back and reread it in a long, long while.)

THE RITUAL IS THE CAB.

Eh-hem. Anyway. She goes on:

Turning something into a ritual eliminates the question, Why am I doing this? By the time I give the taxi driver directions, it’s too late to wonder why I’m going to the gym and not snoozing under the warm covers of my bed. The cab is moving. I’m committed. Like it or not, I’m going to the gym.

The ritual erases the question of whether or not I like it. It’s also a friendly reminder that I’m doing the right thing. (I’ve done it before. It was good. I’ll do it again.)

This bit at the end! The question of “whether or not I like it” immediately countered with the truth that if this ritual is something I have built that will carry me towards things I have decided are meaningful to me, then it will automatically be the right thing.

But even when the right thing has proved, time and time again, to be rich, pleasurable, surprising, rewarding, and thrilling, I still have a brain that fixates on the times it is not. Sometimes it is infuriating, terrifying, or disappointing (although almost always those feelings come at the start, not during the act itself—or after the finish). I latch onto the negatives, drowning in avoidance, believing I can think my way around them.

Tharp’s model requires a clear-eyed statistician’s view—an assessment of the facts. And the fact is I feel good about the act of creation far more often than I feel bad about it. The ritual becomes a method of tipping over the edge into that inexorable slide—the point where it would be far more work to turn back than it is to go forward. The point where you can’t help yourself.

This is the mantra I need going into my next project, quaking in my boots because it all feels new and beyond my capacity or control:

I’ve done it before. It was good. I’ll do it again.

This is an excellent thread that made me laugh uncontrollably for many, many minutes. I share it with you as a gesture of goodwill.

Yours sincerely,

Tiny Sky-Tyrant

P.S. I’ve been working on my marsupial impressions, too.

It’s no good. The sea’s too shallow here—too full of hazardous rocks. I’m threading my way through pudgy, puckered anemones sunk flush with the surface of the sand. It’s getting dark. My car’s parked in a 24-minute parking spot and I’ve already been out here for at least 15.1 I should call it. But I’ll feel bad if I call it. But I should call it.

I try walking down the beach instead, just to feel like I’m choosing something. I know there’s a stretch where the sand smooths out into a gentler and more welcoming crescent, but I misjudge the distance and end up equally far from both my car and the better beach. I jog back along the boardwalk, cursing my indecision through my mask.

I spend several minutes in the car caught in The Waffle—the dreaded space where I justify and wheedle and drive myself batty with excuses and alternatives—until my Wise Self barges in.

You’re not seriously going to drive all the way home and go to bed knowing that you were right here and didn’t do this thing that you KNOW always fills you with an unstoppable sense of power and joy, are you?

Monstrous harpy.

I drive the five minutes down the waterfront, throw the car in the parking lot of the hotel from Little Miss Sunshine, and march past everyone enjoying the last glimmers of sunset. I have a covenant to keep.

I’m bolder with my strip down/stride in routine this time—almost too bold; I nearly enter the water still wearing my mask. A quick return trip to my pile of belongings and I’m running back into the breakers. The water is easy and delicious. It’s not even that cold. Six waves pass before I plunge under the seventh. I stand there staring at the tiniest sliver of a new moon rising on my right for what feels like hours.

She’s right. I’ve never regretted this. Two for two.

1. Why only 24 minutes? Such a specific number. Remind me to look that up later on whatever civic planning blog is nearest. ↩

I got unexpectedly emotional driving home from my COVID test tonight when a line of cars (myself among them) pulled over to let two blaring firetrucks barrel past on their way to make someone’s Very Bad Day less worse.

There it was! An immediate, unspoken acknowledgement that there are more important things going on right now, followed by straightforward collective action to protect and support the people most involved in addressing the crisis at hand.

It doesn’t take a lot, on a day where I’ve passed a boisterous group of twelve unmasked diners on a restaurant patio, to feel overwhelmed seeing people do something that comes from an ethic of mutual care.

I know pulling off the road for 30 seconds isn’t the same as asking the entire populace to avoid human contact for twelve straight months, but I still wish it could be this easy. We’ve clearly figured out how to do this as a society sometimes, y’know? It’s just a question of extending that behavior in a wider circle.

I’m pulling into Santa Barbara, 940 miles of highway behind me, as the sun dips low to the west. On my right: occasional glimpses of the sea, tantalizing and unreal, but ahead there’s only bumper-to-bumper traffic.

I’m racing the clock as I inch through Montecito, drumming my fingers on the steering wheel. The sun’s fully below the horizon by the time the cars thin out, but there’s still time. I’m navigating by instinct across overpasses and down twisty back roads. I’m ignoring the sign that says “Park Closes at 5:30” (it is after 6) and flinging my car across two spaces in my haste to get out. I’m scrambling toward this place I’ve been coming to since I was 3 because I am giddy with disbelief and this is where I need to go to know it’s real.

James calls right as I reach the edge of the sandstone cliff. The sea is mirror-bright and full of sunset. I show him my view (an inadequate FaceTime mockery) and babble about the impossibility of it all. The prickly scrub is catching at my ankles as I stare out at this thing I’ve been unable to feel like I deserve to be near for so long. I realize there’s no time for talking, make my apologies, hang up, and start running down the slanted track to the sand.

There’s barely anyone on the beach as I kick off my shoes. The light’s failing. Everything smells of salt and woodsmoke.

Up close, the colors in the sky and the immensity of the water make me dizzy. I feel simultaneously tiny and expansive. Opening. Unfolding.

What’s the rule?

If I am near a body of water and I can feasibly get into it, I must get into it.

I didn’t think to grab my towel—or my bathing suit, for that matter—but I don’t really care. There isn’t time. I strip to my underwear as the dark closes in and stride toward the water. The sand is gleaming blue with light. The waves are gentle at first, waist high and cold, but I’ve braved worse. I can’t believe I’m here. I shuffle my feet, wary of stingrays, and move deeper, chattering to myself. To the water. To the sunset.

“Hello. Wow. Hi, hello. Oh my god. Hello. I missed you. Okay. Woof. Okay. Okay okay okay here we go. Here we FUCKING GO—“

And then I am under the onrushing breakers and nothing matters anymore. I am not cold. I am not alone. I am not uncertain.

I come up laughing, and I am home.

“I’m so tempted to just go—not tell anyone, just load everything up and leave.”

She narrows her eyes.

“Can we unpack that for a minute?”

Maybe I protest too much, but it’s not what it looks like! I’m no thief in the night! I’m not trying to desert my friends! We do all our socializing on Zoom these days anyway—what difference does it make?

But the truth of the matter is that I want to up and go without any fanfare because I’m dreading the endless cycle of small talk. Why should I keep telling people when the first thing out of anybody’s mouth is “Is it permanent?” and I have to throw my hands up and do the same dance over and over yelling “I don’t know, is anything?!”

The shock in people’s voices also nags at an ongoing pattern of worry: that I have somehow neglected my duty to Keep Everyone Informed.

This happens often: the people closest to me are surprised when I share things that I think I’ve been talking about non-stop, but it turns out I’ve just been thinking them very loudly for a very long time. Not the same thing.

But it is exhausting to always be informing on myself. If I share a thought in progress and then change my mind five more times before coming up with a decision (common), I condemn everyone else to the same vicissitudes of anxiety and overthinking that I’m busy contending with in my own head!

And then even when I have come to a decision, there’s still so much performing. There I am hemming and hawing for the benefit of communicating to other people the complexity of the situation and how I came to this decision and all the factors at play and before I know it I’ve bought into my own mummery. I’m believing the hype that this is terribly difficult and I am terribly conflicted—oh woe is me!—when perhaps if I am quiet and listen only to myself and act only for myself it turns out not to be so difficult or conflict-laden after all.

My word for the year is “flow; or, the sensation I get in the center of my chest when I watch footage of starling murmurations” which, yes, isn’t just one word, but it is a word plus a feeling, or a word distilled from a feeling, which I think still counts. Maybe counts more.

So I am flowing downhill to Ojai. Swimming upstream through my own history to land back where I started. I’m grateful that the blogging urge rekindled when I was down there last summer, because I can see it in my own paper trail—the rightness of this.

I don’t know how to tell everyone, but I do know that tomorrow morning when I am driving south with a car full of unread books, I will feel light, and I will be singing.

I’ve been thinking a lot about about cleverness these last few weeks and how central a thing I think it is in the people I’m drawn to, but also how the term is often used in a slightly perjorative sense. And then of course here comes Ali Smith again just wrecking my shit out of nowhere without a care in the world in the last chapter of There but for the:

“Then she asked Mr. Garth did he really think there wasn’t anything wrong with being cleverest. Top of Mount Cleverest, Mr. Garth said. Brooke laughed. Then Mr. Garth said really slowly:

the fact is, that at the top of any mountain you’ll feel a bit dizzy because of the air up there. Cleverness is great. It’s a really good thing, when you have it. But there’s no point in just having it. You have to know how to use it. And when you know how to use your cleverness, it’s not that you’re the cleverest anymore, or are doing it to be cleverer than anyone else like it’s a competition. No. Instead of being the cleverest, the thing to do is become a cleverist.”

UGH I LOVE THIS WOMAN’S BRAIN.