The other day I was wondering:

The featured snippet that came back at the top of the results rattled my brain for reasons I couldn’t immediately identify.

When I clicked through to the site, long-dormant gears began shifting. It was clearly one of those Internet places that felt unchanged from the early 2000s—the kind of site Robin and I have been yelling enthusiastically at each other about of late—but there was something else. This place was familiar. I’d been here before.

And then it started to come back to me.

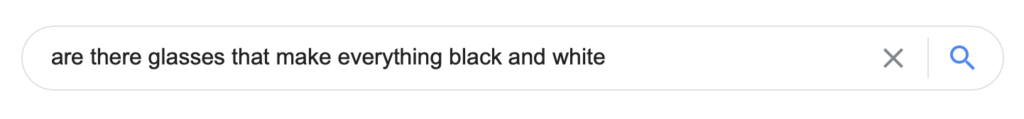

I was a member of Halfbakery. Years ago. When? College? High school? If it was high school I was probably using my typical handle. I plugged it into the site’s search bar.

My profile was still there.

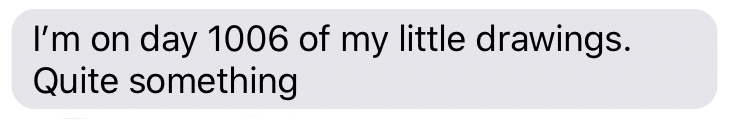

![A screenshot of a profile page from Halfbakery for user "Yarr". It reads:

Yarr

Welcome To Sparknotes!

Plot Summary: Piratical intellectual located under English heritage in Southern California seeks fellow eccentrics for witty banter and theatrical/literary madness.

Central Themes: British humor, Technical theatre, Acting, Pirates, Literature, Silly hats, Silly socks, Silly anything, Good food, Drawing, Insanity, Correct use of punctuation, Triple cream 62% Brie Cheese.

Character Analysis: ...

[Dec 21 2005, last modified Jan 01 2006]](https://lucybellwood.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Screen-Shot-2021-03-15-at-1.12.12-PM-1024x356.png)

I was 15. A baby, all things considered, and one hungry for people who would challenge and excite me. The site was one of those insular places full of smart, sharp users who had developed their own language and culture. Some parts of it, in hindsight, were a bit harsh, others erudite and thrilling. I’d posted two ideas which were roundly downvoted by the community at large, but I kept up as a reader. I won’t pretend I went on to become a cornerstone of the community—because I didn’t—but the site clearly stuck in my memory enough to feel familiar when I found it again.

The kicker isn’t just that it’s still going, but that there’s been relatively little (if any) alteration to the interface since I first encountered it in 2005. I barely recognize Facebook if I log in after an absence of three months, let alone sixteen years. This felt like walking into my childhood bedroom and finding things exactly as I left them.

I poked around for a while, seeing ideas from 2006 and 2021 jostling shoulder to shoulder. Eventually I stumbled down a rabbit hole of in memoriam posts for members who had passed away.

Because that’s what happens when you run a community for 22 years. Some of your users will probably die. And if you’ve built a sense of camaraderie and mutual regard, their absence will be felt keenly by a collection of strangers who never knew them anywhere other than this niche, textual space.

A little family in the wilderness. What an odd gem of a thing.

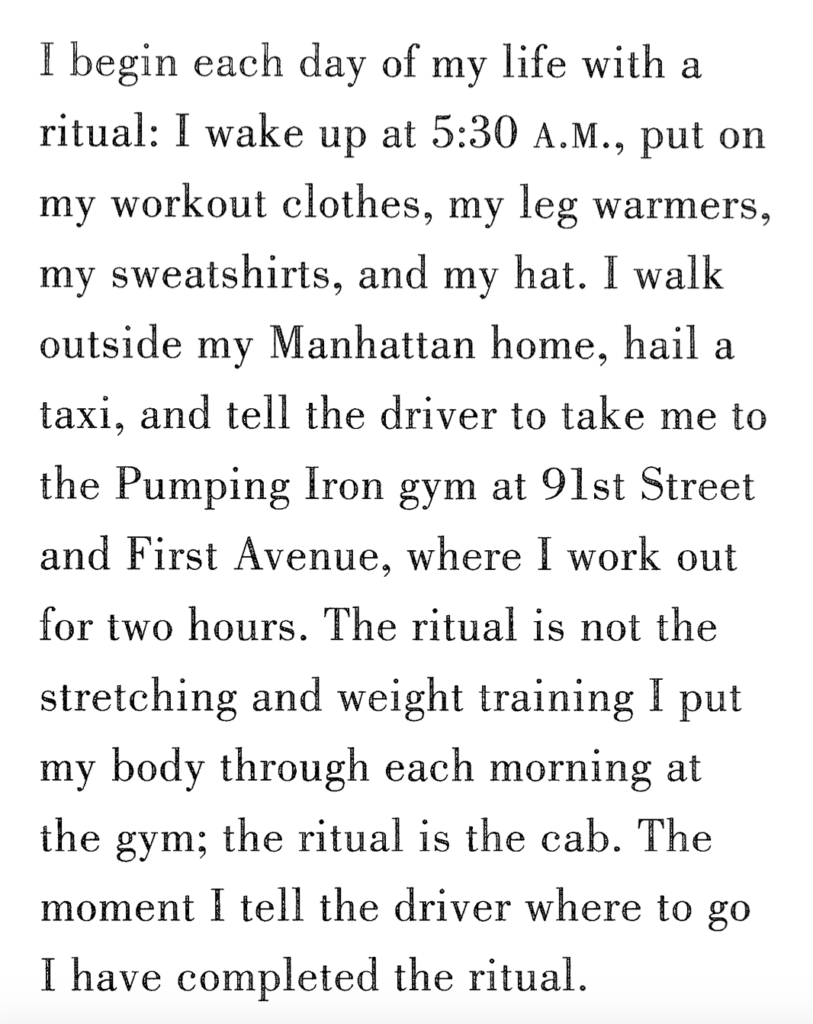

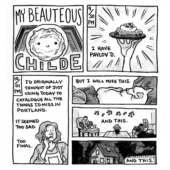

![A complex mind map connecting various names and creative works of nine people, mostly female writers.

The following themes are positioned throughout the page like nodes:

[See Me / Don’t See Me]

[Gardening]

[Queer Relationships]

[Utopia]

[Solitude]

[Fluidity]

[Rhythm]

Ursula K. (Kroeber) Le Guin 1929 - 2018

“The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction" 1988 in Women of Vision

2010: Began [Age 81] Blogging

No Time to Spare (pub. 2017, HMH)

A left-handed Commencement Address, 1983 Mills College

The Wave in The Mind (pub. 2004, Shambhala)

Epigraph: “As for the mot juste, you are quite wrong. Style is a very simple matter: it is all rhythm. Once you get that you can't use the wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting after half the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and can't dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it, and in writing (such is my present belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which has nothing apparently to do with words) and then as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it. But no doubt I shall think differently next year.” (Woolf to Sackville-West, 1926).

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941)

1931 Professions For Women

“It is a very strange thing that people will give you a motor car if you will tell them a story. It is a still stranger thing that there is nothing so delightful in the world as telling stories."

"The Angel in the house"

Orlando

The Waves

1929 Room of One’s Own

Met Sackville-West in 1922

Gail Godwin (b. 1937)

1977 (NYT) The Watcher at the Gates

12 Short Stories and Their Making (2005, Persea)

Appeared with Le Guin in same publication

“A story larger than my own” Working On An Ending, 2014

"Now I do a lot of lying around. I finally I have accepted that my supine dithering is fertile and far from a waste of time"

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) <-> Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962)

Nigel Nicolson (1917-2004)

Portrait Of A Marriage (1973)

Not to be confused with

Nigel Nicholson -> [Classics] [Reed College]

"The Bright Chimera" R. Rawdon Wilson

Olivia Laing (1977-)

Married Ian Patterson (1948) in 2018 [29 years apart!]

May Sarton (1912-1995)

(At Yaddo) "I hated all the shop talk. I'd rather see people who are carpenters, who are sailors or who work in healthy departments, because then I feel I am learning something about life."

“There is much less anguish and self-doubt. You are much more able to function freely, spontaneously, as yourself."

met Woolf in 1937](https://lucybellwood.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IMG_5457-scaled.jpeg)